Read an extract from A Boy Made of Blocks by Keith Stuart

Chapter 1

I am estranged.

This is the first thought that hits me as I leave the house, cross the road and climb into our battered old estate car. I guess the correct term is we are estranged, but then mostly, I suppose, this is my fault. I look back through the rear- view mirror and see my wife, Jody, in the doorway, her long hair dishevelled and knotted. Burying his head into her side is our eight- year- old son, Sam. He is trying to simultaneously cover his eyes and his ears, but I know it’s not because he doesn’t want to see me go. He is anticipating the sound of the engine, which will be too loud for him.

I raise my hand in a dumb apologetic gesture, the sort you make when you accidentally pull out in front of someone at a junction. Then I turn the key and start to pull slowly away. The next thing I know, Jody is at the driver- side window, knocking gently. I wind it down.

‘Take care of yourself, Alex,’ she says. ‘Please figure things out – like you should have done years ago, when we were happy. Perhaps if you had . . . I don’t know. Perhaps we’d be happy now.’

Her eyes are moist and she angrily wipes away a tear with the back of her hand. Then she is looking at me, and it seems the expression on my face, of sorrow, of guilt, suddenly impacts on her anger. Her glistening stare becomes something softer.

‘Remember that camping holiday we went on in Cumbria?’ she says. ‘The one where those goats ate our tent and you got trench foot? Whatever’s happening here, it’s not as bad as that, OK?’

I nod silently, put the car into gear and start heading up the road. When I check the mirror again, I see that Jody and Sam have already gone back in. The front door is closed.

That’s it. Ten years together and it could all be over. And now I’m in our crappy car, driving away, and I have no idea where I’m going.

Sam was a beautiful baby. He was always beautiful. He was born with thick brown hair and these big sultry lips – like a tiny incontinent Mick Jagger.

Right from the start he was difficult. He wouldn’t feed, he wouldn’t sleep. He cried and cried; he cried when Jody held him and he cried when he was taken away. He seemed livid to be in the world. It was over a day before he finally managed to take in some milk. Shattered and desperate, Jody held him to her breast and bawled with relief. I looked on haggard and confused, clutching a Sainsbury’s bag full of chocolate bars and magazines; useless treats for the new mum. I realised very quickly there was nothing I could give her to make this easier. This was it. This was life now.

It was such a rush.

‘You can stay for as long as you like, dude,’ says Dan, when I inevitably turn up at his flat twenty- three minutes later. I knew Dan would be there for me – or at least I knew he’d actually be home on a Sunday afternoon because he is usually recovering from something – a club opening, a casual sexual encounter, or some exciting combination of those two.

‘You can stay in the spare room,’ he says as we get into the lift. ‘I’ve got an inflatable mattress somewhere. I think it may have a leak, though. Actually, they all leak, don’t they? Have you ever slept on an inflatable mattress that didn’t leak? Am I right? Sorry, man, you’re not ready to think about this now. Got it.’

Then I’m standing in his doorway, feeling dumbfounded, still holding my Nike sports bag, which contains all my clothes, my laptop, some CDs (why?), a washbag and a photo I took of Jody and Sam on holiday in Devon four years ago. They are sitting on a beach smiling, but it is a terrible charade. The whole week was a complete nightmare because Sam couldn’t sleep in the weird new bed with its heavy unfamiliar blanket, and also he was completely terrified of seagulls. So he slept with us, fidgeting and waking all night – every night – until we were so tired we could barely leave the caravan. We didn’t go on holidays much after that.

‘Do you want to go out and get drunk?’ offers Dan.

‘I . . . is it OK if I put my stuff in the room and sort of sit down for a bit?’

‘Sure, yes. I’ll put the kettle on. I think I have biscuits. I’m pretty sure I have biscuits.’

Dan heads off toward the kitchen and I trudge into the spare room, chuck my bag on the floor and slump into the office chair next to his computer. For a moment, I consider firing it up and emailing Jody, but instead I gaze out of the window. I mean, what would I write? ‘Hey, Jody, sorry about fucking up our marriage. Any chance we could forget the last five years? ROFL.’

Truth is, I don’t even know how to talk to her any more, let alone write to her. We’ve basically spent our whole marriage worrying about Sam – his outbursts, his silence, the days he’d scream at us, the days he’d hide in his bed and shrink from any contact at all. Days and days, stretching out to months, trying to anticipate the next breakdown. And while we were coping with all that, the things that Jody and I had together somehow faded away. Now, being away from Sam, even for only a few hours, is weird; the pressure is gone, but in its place a sorrow is already flooding. Nature abhors an emotional vacuum.

From Dan’s seventh- floor flat in a smart new complex on the edge of the city, you can see the whole of Bristol stretching toward the horizon: a cobbled panorama of Victorian terraces, church spires and sixties office blocks, all shoving at each other like impatient commuters. There are thousands of homes out there filled with families – families that haven’t this minute split apart.

I start to think that maybe a drink would be a good idea. But even as I’m contemplating it, my eyes become blurry and it takes me a few seconds to catch on to what is happening. Oh. Oh right, I’m crying. And then there are these giant tears running down my face, leaving hot moist streaks, and my nose is bubbling with snot, and I’m shaking.

‘Tea’s up!’ says Dan from the hallway. ‘I thought I had chocolate Hobnobs but all I could find was this packet of Rich Teas. I’m not sure if that’s going to do the trick?’

He appears in the doorway, looks down and sees me cross- legged on the floor by the chair, head in hands, sobbing madly.

‘Right, OK,’ he says, gently putting the tea down on the desk. ‘I’ll have another look for those Hobnobs.’

We decide not to get drunk.

Later that night, I dream that I’m sinking into a terrible black swamp from which there is no escape. When I wake up gasping for air, I’m convinced this must be some desperate manifestation of my emotional state – but then I realise the mattress is rapidly deflating and I am literally sinking. So much for the subconscious.

‘How did I get here?’ I ask myself as the escaping air makes intermittent rasping sounds like a flatulent puppy. You know what it’s like, weighing up your life at 3 a.m.: everything contracts around the mistakes you’ve made, the fissures of failure running back through time, like cracks in a badly plastered wall – even in the darkness you can trace them all the way to the source. Or at least you think you can. It usually turns out that the source is evasive and endlessly shifting – like the puncture on an inflatable mattress. The Ancient Greek philosophers had this phrase, ‘know thyself’.

I remember studying Oedipus at university – his big crime was to not know that he had been separated from his parents at birth and therefore he should be extra careful about killing strange men on the road and then shagging women twice his age. But who really knows themselves? I mean, I’m not saying we’re all going to make the lifestyle errors that Oedipus made – that’s fucked up. But who genuinely knows why we do the things we do? I am stuck in a job I hate, working long hours, trudging home in the dark, and I tell myself this is because we need the money, we need security. Sam is having speech therapy, and Jody can’t work because he needs her constantly; it’s her he runs to when his own behaviour terrifies him. I stand awkwardly in the background, worrying, offering help that isn’t helpful. How can I connect everything again?

Somehow, at around 4 a.m., I fall into a state of semi-consciousness that I’ll be generous and call sleep. In what seems like minutes, though, light is flooding in through the blinds and it is Monday morning and Dan is at the door in a tight pair of black Calvin Klein boxer shorts, scoffing hungrily from a bowl of Frosties.

‘Are you going to work?’ he asks. ‘I can leave a key. I’ve got to go in, like, ten minutes. I’m helping Craig with a website he’s building . . . for this music label in Stokes Croft. You can help yourself to cereal and coffee. Are you OK? You look a bit better. I mean, you look like shit, but at least you’re not crying.’

He disappears into the shower. I check my phone; there are two text messages, but neither of them are from Jody. They are from Daryl at work. One says, Get yr ass into work, I’ve got two new victims for you. The follow up says, Sorry, I mean ‘clients’. I delete them both.

Then I’m dressed and outside and trudging toward town. The sun is low and bright over the apartment buildings, its light reflecting off the glass and glaring concrete. Twenty years ago, this area was all crumbling factories and empty lots, strewn with rubbish and buried under crawling weeds. Then the economy stirred, and suddenly it’s prime real estate. Before you know it, the whole area is futuristic residential zone, a giant circuit board of faux- Brutalist apartment blocks, jammed with capsule flats for young professionals on the make.

I’ve met a lot of these people. I helped them live here. I am, for my many sins, a mortgage adviser. My job is to measure the hopes and dreams of our clients against both the property market and the savings they have accumulated. In other words I get people to swap everything they’re ever going to earn for a studio flat in which

you couldn’t even swing a photo of a cat that you’ve downloaded on to your smartphone. This is a strangely parental job – let’s work out what you have and what you can afford; let’s not over- stretch, we have to be sensible. What assets do you have? Do you have any wealthy relatives? We work through budgets together. Young couples who have recently married, or have a baby on the way, pooling their meagre resources. They look at me with pathetic hope. Is this enough? Often it isn’t. The only answer is to rent for a few more years, save up. I go through these routines every day. The system is busted; I’m seeing whole neighbourhoods where youngsters don’t stand a chance of buying. Instead they’re moving far away from their families. I don’t know where.

I’ve been here eight years, all through the boom and the recession and the nascent recovery. It was meant to be a stopgap. An office job to pay the bills until something better cropped up. But I slipped on to a career path and couldn’t get up. Turns out I’m good at it – sympathetic with the poor, helpful to the rich. I am very patient with clients who don’t understand what they’re talking about – a skill learned from spending three years debating philosophy with people who thought Nietzsche had a point. When the finances align, I can close the deal; when they don’t, I let the customer down gently. Whatever is happening at home, though, I can’t fix that with a computer and access to the national mortgage market.

I can’t fix it at all.

A short walk over the Avon, and along the harbour front, and I’m at the office, a small independent estate agent named Stonewicks, tucked between a pub and a sandwich shop in a dense, unfashionable quarter of the city centre. Daryl is here, sitting nearest the window, his cheap Top Man suit radiating static, his spiky hair damp and wilting in the reflected sunlight.

‘Oright, mate?’ he says from his desk, without looking up from the computer. Daryl is in his early twenties and gives off an air of studied determination while still managing to remain nightmarishly chirpy at all times. This guy literally could not have done any other job than estate agent. There is a spreadsheet on his computer somewhere that maps out his sales targets for the next thirty years. He honks a fucking bicycle horn when a property deal completes. It’s almost tragic that Daryl was born in the nineties and not the late sixties. He should have been a young Thatcherite. He deserves a bulging Filofax and a Golf GTI. Instead he has a smartphone and a Corsa. I feel for him.

I mumble a reply and head up the creaky wooden stairs to my office. And then I call Jody.

‘Hi, it’s me.’

‘Hi.’

‘How are things? How is Sam?’

‘He’s fine. He’s at school. He cried all the way there – even after I did all the Toy Story impressions. He punched me in the mouth during Buzz Lightyear. To be fair, it’s not my best. Mrs Anson said she’d look after him.’

‘Are you OK?’ I ask.

There’s a long pause. Jeanette, the secretary, pops her head in and mimes drinking from a mug. I nod and make a thumbs up.

The office is bare. A worn claret carpet, a grubby window overlooking the small car park to the rear of our building. There used to be a painting of Victorian Bristol on the wall, but I took it down and hung a photo of Corbusier’s Villa Savoye to make myself feel clever and piss everyone off. There is a filing cabinet and on top of that, a dozen thank you cards from young couples setting out in the world with their enormous debts.

‘So what are we doing?’ Jody says.

‘I don’t know. I’ve never run away from home before. Look, I’m sorry, I’ve got to go – there’s another couple coming in.’

As I slam the phone down, Jeanette arrives with the tea. She quietly puts the drink down on the desk, shoots me a sympathetic look and leaves. She’s heard everything. The rest of the office will know within ten minutes. I left my wife and my autistic son.

I think I’ve escaped from the domestic torment for a while, but I’m wrong. An hour later I head into town for lunch, and pop into a little sandwich place Jody and I used to bring Sam to. Amid the midday hustle, I spot Jody sitting at a table with her friend Clare. They are conspiratorially hunched over two medium lattes. I approach, nudging my way through the young mums and students. They haven’t seen me.

‘He’s become so distant,’ Jody is saying. ‘I can’t depend on him at all at home. There’s always something else.’

‘Has he looked into counselling?’ asks Clare. ‘I mean, has he ever dealt with what happened to him?’

Of course, Jody and Clare talk about everything. Of course, they are here at lunchtime dissecting our relationship. They have that effortless unguarded frankness that most men are incapable of. You know: ‘Have some of this lemon cake, it’s lovely, and also, tell me more about the emotionally apocalyptic disintegration of your nine-year marriage.’

‘Hi,’ I say pathetically.

They both look up, slightly shocked.

‘Oh, hi, Alex,’ says Clare. ‘We were just talking about you.’

‘I heard,’ I say. ‘Can I have a quick word with Jody?’

‘Sure, I was heading off anyway. Jody, I’ll see you later, OK?’

Jody nods silently. I sit down. She plays with the empty sugar sachet by her cup.

‘I guess Clare knows everything then?’ I say.

‘Yes, I was upset, and I need to talk to my friends, Alex. We don’t talk. We can’t live like that any more. I’m so tired. I’m so very tired of it all.’

‘I know, I know. I’ve been needed a lot at work, that’s all; we’re under so much pressure. I’m sorry I’ve not been there for you and Sam; I’m sorry I’m backing out of looking after him. It’s all so . . . ’

‘Hard?’ Jody finishes. ‘Damn right it is, Alex. It’s fucking hard. But he needs you.’

‘You know how sometimes we go through weeks and he’s fine? He’s adorable. Then for no reason it goes back. That’s the worst thing. I always think we’ve turned a corner. It’s all that going on, and work—’

‘Oh, Alex, it’s not work, it’s you.’

‘I know.’

‘This is why, Alex. This is why I need some time. Sam can’t cope with us shouting at each other. Mum has offered to stay for a bit if I need help, and Clare is around. You have to sort yourself out.’

‘What about Sam and his school? We’ve only got a few months to decide if we’re going to try and move him.’

What about Sam? Oh, how those words have echoed around our lives. Sam is the planet of concern and confusion that we have been orbiting for most of our relationship. Last year the paediatrician told us, after interminable months of tests and interviews, that he is on the upper end of the autism spectrum. The higher functioning end. The easy end. The shallow end. He has trouble with language, he fears social situations, he hates noise, he obsesses over certain things, and gets physical when situations confuse or frighten him. But the underlying message seemed to be: you’ve got it easy compared to other parents.

And yes, the diagnosis was a relief. At last, a label! When he’s screaming and fighting on the way to school; when he hides under the table at restaurants; when he refuses to hug or acknowledge relatives or friends or anyone but Jody, it’s autism. Autism did it. I started to see autism as a sort of malevolent spirit, a poltergeist, a demon. Sometimes it really is like living in The Exorcist. There are days it wouldn’t surprise me if his head started spinning in 360-degree revolutions while he vomited green slime across the room. At least I could say, ‘It’s OK, it’s autism – and that green slime comes off in a hot wash.’ But labels only get you so far. They don’t help you sleep, they don’t stop you from getting angry and frustrated when something gets thrown at you, or broken. They don’t stop you fretting about your child and their life; what will happen to them in ten years, or twenty, or thirty. Because of autism, there is no Jody and I, there is Jody, me and the problem of Sam. That’s how it feels. But I can’t say that. I can barely think it.

‘With Sam and everything . . . ’ I can’t finish, but it’s enough.

‘I know. But you need some help. Or you need to start dealing with things. Why don’t you come over on Saturday and see him? Come and take him out.’

I fumble with my phone, turning it over in my hand. I see Sam at the park, crying, running away. Running through the gate. Running into the road.

‘It could be tricky, I may be needed at work.’

But I see the steel in her eyes, a flash of fury obvious even amid the clatter of the café.

‘Yes, sure,’ I say.

‘We can talk about schools then.’

‘Yes. Let’s do that.’

‘Goodbye, Alex. Take care.’

‘You too. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.’

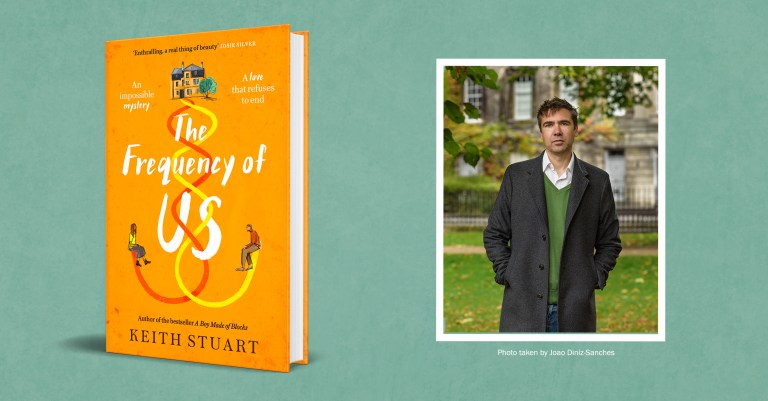

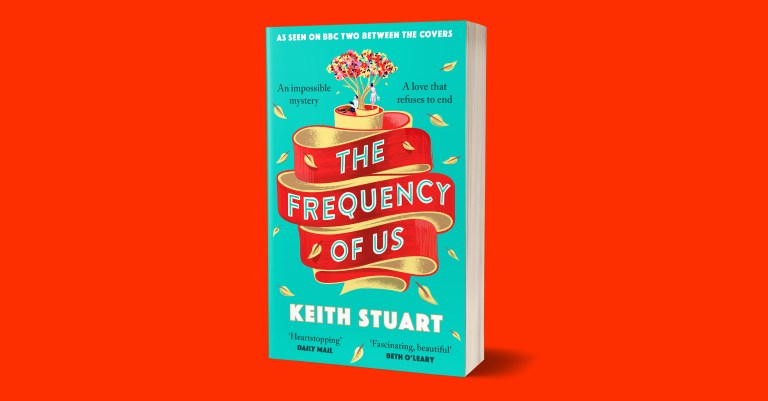

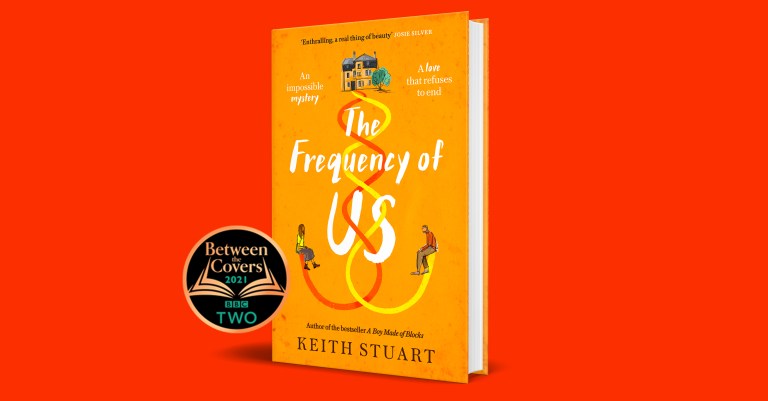

THE RICHARD AND JUDY BOOK CLUB AND NUMBER ONE AMAZON BESTSELLER

'The publishing sensation of the year: a compelling, uplifting and heart-rending debut novel'

Mail on Sunday

A Boy Made of Blocks is a funny, heartwarming story of family and love inspired by the author's own experiences with his son, the perfect latest obsession for fans of The Rosie Project, David Nicholls and Jojo Moyes.

A father who rediscovers love

Alex loves his wife Jody, but has forgotten how to show it. He loves his son Sam, but doesn't understand him. He needs a reason to grab his future with both hands.

A son who shows him how to live

Meet eight-year-old Sam: beautiful, surprising - and different. To him the world is a frightening mystery. But as his imagination comes to life, his family will be changed . . . for good.

'One of those wonderful books that makes you laugh and cry at the same time'

Good Housekeeping

'Funny, expertly plotted and written with enormous heart. Readers who enjoyed The Rosie Project will love A Boy Made of Blocks - I did'

Graeme Simsion

'Very funny, incredibly poignant and full of insight. Awesome.'

Jenny Colgan

'Heartwarming'

The Unmumsy Mum

'A wonderful, warm, insightful novel about family, friendship and love'

Daily Mail

'A great plot, with a rare sense of honesty'

Guardian

'A truly beautiful story'

Heat

'A heartwarming and wise story'

Cathy Rentzenbrink, author of The Last Act of Love