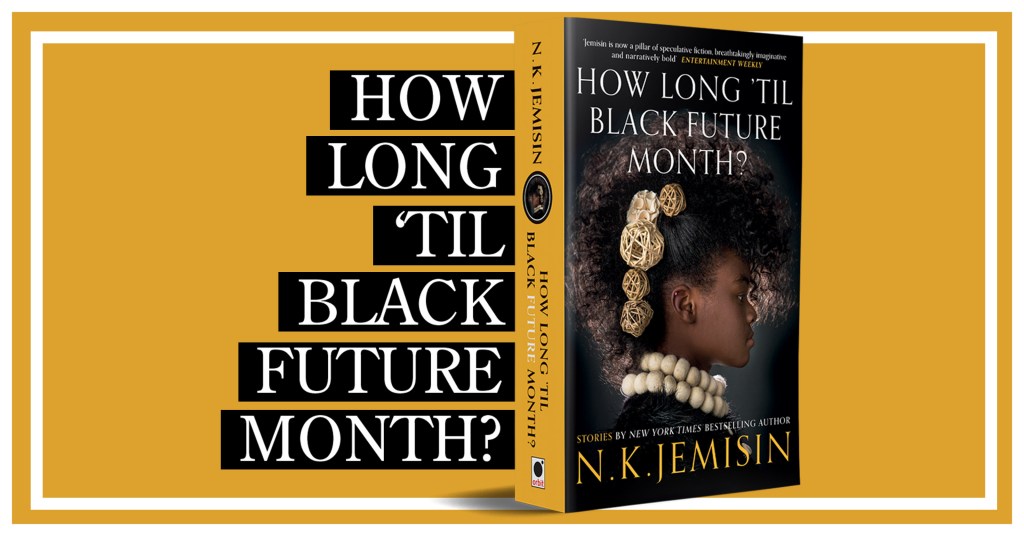

Read an extract from How Long ’til Black Future Month by N. K. Jemisin

This Black History Month let us ask How Long ‘Til Black Future Month?

Read an extract from triple Hugo Award-winning and New York Times bestselling author N. K. Jemisin’s short story collection.

N. K. Jemisin is one of the most powerful and acclaimed speculative fiction authors of our time. In the first collection of her evocative short fiction, Jemisin equally challenges and delights readers with thought-provoking narratives of destruction, rebirth, and redemption.

In these stories, Jemisin sharply examines modern society, infusing magic into the mundane, and drawing deft parallels in the fantasy realms of her imagination. Dragons and hateful spirits haunt the flooded streets of New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. In a parallel universe, a utopian society watches our world, trying to learn from our mistakes. A black mother in the Jim Crow South must save her daughter from a fey offering impossible promises. And in the Hugo award-nominated short story “The City Born Great,” a young street kid fights to give birth to an old metropolis’s soul.

Introduction

Once upon a time, I didn’t think I could write short stories.

The time was 2002. I’d just turned thirty and had my first “midlife” crisis. (Yeah, I know.) I was living in Boston, where it was cold and hard to make friends and nobody put seasoning on any-thing. I’d just ended a lackluster relationship, and I was in student loan debt up to my eyeballs, like pretty much everybody else in my generation. In an attempt to resolve frustration with the state of my life, I finally decided to see whether my lifelong writing hobby could be turned into a side hustle worth maybe a few hundred dollars. If I could make that much (or even just one hundred a year!), I might be able to cover some of my utility bills or something. Then I could get out of debt in twelve or thirteen years, instead of fifteen.

I wasn’t expecting more than that, for reasons beyond pessimism. At the time, it was clear that the speculative genres had stagnated to a dangerous degree. Science fiction claimed to be the fiction of the future, but it still mostly celebrated the faces and voices and stories of the past. In a few more years there would come the Slushbomb, an attempt by women writers to improve one of the most sexist bastions among the Big Three; the Great Cultural Appropriation Debates of DOOM; and Racefail, a thousand- blog storm of fannish protest against institutional and individual racism within the genre. These things collectively would open a bit more room within the genre for people who weren’t cishet white guys— just in time for the release of my first published novel, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms. But back in 2002 there was none of that. In 2002, I knew that as a black woman drawn to science fiction and fantasy, I had almost no chance of getting my work published, noticed by reviewers, or accepted by a readership that seemed to want nothing more than endless variations on medieval Europe and American colonization. And while I could’ve sharted out my own variation on medieval Europe or American colonization — and probably should have, if I wanted to pay off my loans faster — that just didn’t interest me. I wanted to do something new.

Established writers advised me to attend one of the Clarions or Odyssey, but I couldn’t; the day job only allowed me two weeks of vacation time. Instead, I borrowed six hundred dollars from my father and attended Viable Paradise, a one- week workshop out on Martha’s Vineyard. Since a week isn’t really enough time to substantively improve attendees’ writing, VP focused on other stuff — like how to make it in the business of fiction. I learned tons about getting an agent, the publication process, and how to survive as a writer; it was exactly what I needed at that stage of my career. And there I was given one more really good piece of advice: learn to write short stories.

This was the only VP advice that I balked at, because it sounded completely nonsensical to me. I’d read some short stories over the years, and enjoyed a few, but never felt the urge to write any. I knew enough to argue that short stories were a completely different art form from novels, so shouldn’t I spend my limited free time refining the thing I wanted to do, rather than learning this other thing that honestly seemed kind of boring? Also, I knew that the pay rate for short stories was abysmal; this was in the days when the SFWA- acceptable rate for pro- level markets was only three cents per word. Remember, one of my goals was utility- bill money. Short stories, assuming I sold any, wouldn’t even cover the cooking gas.

But the instructors at VP* made a compelling case. The argument that finally convinced me was simply this: learning to write short fiction would improve my longer fiction. I didn’t know whether to believe this or not, but I decided to spend a year find-ing out. For that year, I subscribed to F&SF and the now-defunct Realms of Fantasy, read online markets like Strange Horizons, and joined a writing group. The project didn’t go well at first. My first “short” story was a whopping 17,000 words and had no ending. But I got better. When I started submitting those stories to magazines, I got lots of rejections. My writing group helped me see that rejections are part of writing; we collected them, in fact, and tried to celebrate them along with the acceptances. Then I started getting acceptances— semipro markets at first, and then finally pro sales.

And along the way, I learned that short stories were good for my longer-form fiction. Writing short stories taught me about the quick hook and the deep character. Shorts gave me space to experiment with unusual plots and story forms — future tense, epistolic format, black characters — which otherwise I would’ve considered too risky for the lengthy investment of a novel. I started to enjoy writing short fiction, for itself and not just as novel practice. And of course, after all those rejections, my emotional skin grew thick as an elephant’s.

But wait. Back up. Yeah, I said black characters. I had done those before in novels I wrote as a teenager, which will never see daylight, but I’d never submitted anything with black characters. Remember how I described the industry circa 2002. Editors and publishers and agents talked a good game back then about being “open to all perspectives,” as they vaguely termed it, but the proof wasn’t in the pudding. To see the truth, all I had to do was open a magazine’s table of contents, or a publisher’s web page, to see how few female or “foreign” names were in the author list. When I sampled a particular publisher’s novels or stories for research, I paid attention to how many — or how few — characters were described as something other than white. I still wrote black characters into my work because I couldn’t stand excluding myself from my own damn fiction. But if the goal was to make money . . . well, like I said. I didn’t expect much.

So I lack the words to tell you how powerful a moment it was for my first pro sale — “Cloud Dragon Skies,” published in Strange Horizons in 2005 — to be about a nappy-haired black woman trying to save humanity from its own folly.

How Long ’til Black Future Month takes its name from an essay that I wrote in 2013. (It’s not in this collection since I haven’t included any essays; you can find it on my website, nkjemisin.com.) It’s a shame-less paean to an Afrofuturist icon, the artist Janelle Monáe, but it’s also a meditation on how hard it’s been for me to love science fiction and fantasy as a black woman. How much I’ve had to fight my own internalized racism in addition to that radiating from the fiction and the business. How terrifying it’s been to realize no one thinks my people have a future. And how gratifying to finally accept myself and begin spinning the futures I want to see.

The stories contained in this volume are more than just tales in themselves; they are also a chronicle of my development as a writer and as an activist. On rereading my fiction to select pieces for this collection, I’ve been struck by how hesitant I once was to mention characters’ races. I notice that many of my stories are about accepting differences and change . . . and very few are about fighting threats from elsewhere. I’m surprised to realize how often I write stories that are talking back at classics of the genre. “Walking Awake” is a response to Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters, for example. “The Ones Who Stay and Fight” is a pastiche of and reaction to Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas.”

If you’re coming to these tales as someone who primarily knows me through my novels, you’re going to see the early forms of plot elements or characters that later got refined in novels. Sometimes that’s deliberate, since I write “proof of concept” stories in order to test-drive potential novel worlds. (“The Narcomancer” and “Stone Hunger” are examples of this; so is “The Trojan Girl,” but I decided not to write a novel in that world, instead finishing it up with “Valedictorian.”) Sometimes the “re-versioning” is completely unconscious, and I don’t realize I’ve trodden familiar ground until long after. The world of the Broken Earth trilogy wasn’t my first time playing with genii locorum, for example — places with minds of their own. The concept appears in several of my stories, sometimes flavored with a dash of animism.

Anyway, things are better these days. I paid off my student loans with my first novel advance. As of this writing I live as a full-time writer in New York, where I have lots of friends and my fiction brings in considerably more than utility bill money. (Even at Con Ed rates.) Right now in 2018, the genre seems at least willing to have conversations about its flaws, though there’s still a long way to go before any of those flaws are actually repaired. At least I see more “foreign” and femme names on book spines and in tables of contents these days.

I see readers demanding fiction featuring different voices, spoken by native tongues, and I see publishers scrambling to answer. And while the voices of dissent have grown as well — bigots trying to rewrite history and claim the future for themselves alone — they are in the severe minority. The rest of the world has administered some truly beautiful clapbacks to remind them of this.

Now I mentor up-and-coming writers of color wherever I find them . . . and there are so many to find. Now I am bolder, and angrier, and more joyful; none of these things contradict each other. Now I am the writer that short stories made me.

So come on. There’s the future over there. Let’s all go.

* At the time, Patrick and Teresa Nielsen Hayden, Debra Doyle, James MacDonald, James Patrick Kelly, and Steven Gould.