Read an extract from The Bottle Factory Outing by Beryl Bainbridge

Shortlisted for the Booker Prize and named ‘one of the greatest novels of all time’ by the Observer, this riveting novel shows Beryl Bainbridge at her darkly comic best

‘An outrageously funny and horrifying novel’ Graham Greene

‘Superb… taut in construction, expansive in characterisation, vibrant in atmosphere and profoundly comic’ The Times

‘The masterful restraint of Beryl Bainbridge’s sentences reveals an author in complete control of her artistry’ Guardian

‘Two very complex, funny female characters. They need each other although they would never admit it’ Maxine Peake

1

The hearse stood outside the block of flats, waiting for the old lady. Freda was crying. There were some children and a dog running in and out of the line of bare black trees planted in the pavement.

‘I don’t know why you’re crying,’ said Brenda. ‘You didn’t know her.’

Four paid men in black, carrying the coffin on their shoulders, began to walk the length of the top landing. Below, on the first floor, a row of senior citizens in nighties and overcoats stood on their balconies ready to wave the old woman goodbye.

‘I like it,’ said Freda. ‘It’s so beautiful.’

Opulent at the window, she leant her beige cheek against the glass and stared out mournfully at the block of flats, moored in concrete like an ocean liner. Behind the rigging of the television aerials, the white clouds blew across the sky. All hands on deck, the aged crew with lowered heads shuffled to the rails to watch the last passenger disembark.

Freda was enjoying herself. She stopped a tear with the tip of her finger and brought it to her mouth.

‘I’m very moved,’ she observed, as the coffin went at an acute angle down the stairs.

Brenda, who was easily embarrassed, didn’t care to be seen gawping at the window. She declined to look at the roof of the hearse, crowned with flowers like a Sunday hat, as the coffin was shoved into place.

‘She’s going,’ cried Freda, and the engine started and the black car slid away from the kerb, the gladioli and the arum lilies trembling in the breeze.

‘You cry easily,’ said Brenda, when they were dressing to go to the factory.

‘I like funerals. All those flowers – a full life coming to a close . . .’

‘She didn’t look as if she’d had a full life,’ said Brenda.

‘She only had the cat. There weren’t any mourners – no sons or anything.’

‘Take a lesson from it then. It could happen to you. When I go I shall have my family about me – daughters – sons – my husband, grey and distinguished, dabbing a handkerchief to his lips . . .’

‘Men always go first,’ said Brenda. ‘Women live longer.’

‘My dear, you ought to participate more. You are too cut off from life.’

When Freda spoke like that Brenda would have run into another room, had there been one. Uneasily she said,‘I do participate. More than you think.’

‘You are not flotsam washed up on the shore, without recourse to the sea,’ continued Freda. She was lifting one vast leg and polishing the toe of her boot on the hem of the curtains. ‘When we go on the Outing you bloody well better participate.’

‘I can’t promise,’ said Brenda rebelliously.

Unlike Freda, whose idea it had been, the thought of the Outing filled her with alarm. It was bound to rain, seeing it was already October, and she could just imagine the dreary procession they would make, forlornly walking in single file across the grass, the men slipping and stumbling under the weight of the wine barrels, and Freda, face distorted with fury at the weather, sinking down on to the muddy ground, unwrapping her cold chicken from its silver foil, wrenching its limbs apart under the dripping branches of the trees. Of course Freda visualised it differently. She was desperately in love with Vittorio, the trainee manager, who was the nephew of Mr Paganotti, and she thought she would have a better chance of seducing him if she could get him out into the open air, away from the bottling plant and his duties in the cellar. What she planned was a visit to a Stately Home and a stroll through Elizabethan gardens, hand in hand if she had her way. The men in the factory, senses reeling at the thought of a day in the country with the English ladies, had sent their Sunday suits to the cleaners and told their wives and children that the Outing was strictly for the workers. Rossi had given Freda permission to order a mini-coach; Mr Paganotti had been persuaded to donate four barrels of wine, two white and two red.

‘You should be terribly keen,’ said Freda. ‘All that fresh air and the green grass blowing. You should be beside yourself at the prospect.’

‘Well, I’m not,’ said Brenda flatly.

Freda, who longed to be flung into the midst of chaos, was astonished at her attitude. When they had first met in the butcher’s shop on the Finchley Road, it had been Brenda’s lack of control, her passion, that had been the attraction. Standing directly in front of Freda she had asked for a pork chop, and the butcher, reaching for his cleaver on the wooden slab, had shouted with familiarity ‘Giving the old man a treat are you?’ at which Brenda had begun to weep, moaning that her husband had left her, that there was no old man in her world. She had trembled in a blue faded coat with a damaged fur collar and let the tears trickle down her face. Freda led her away, leaving the offending cut of meat on the counter, and after a week they found a room together in Hope Street, and Freda learnt it wasn’t the husband that had abandoned Brenda, it was she who had left him because she couldn’t stand him coming home drunk every night from the Little Legion and peeing on the front step. Also, she had a mother-in-law who was obviously deranged, who sneaked out at dawn to lift the eggs from under the hens and drew little faces on the shells with a biro.

It was strange it had happened to Brenda, that particular kind of experience, coming as she did from such a respectable background – private school and music lessons and summer holidays playing tennis – exchanging her semi-detached home for a remote farmhouse in Yorkshire, lying in a great brass bed with that brute of a husband, and outside the wild moors, the geese and ducks in the barn, the sheep flowing through a gap in the wall to huddle for warmth against the sides of the house. She was so unsuited for such a life, with her reddish hair worn shoulder-length and stringy, her long thin face, her short-sighted blue eyes that never looked at you properly, while she, Freda, would have been in her element – there had been white doves on the outhouse roof.

It was unfair. She told her so. ‘I always wanted to live in a house with a big kitchen. I wanted a mother in a string vest and a pinny who made bread and dumpling stew.’

‘A string vest?’ said Brenda dubiously, and Freda couldn’t explain – it would have been wasted on her.

Since that first outburst in the butcher’s shop, Brenda had become withdrawn and unemotional, except for her delusion that men were after her. Freda had hoped working in a factory would enrich Brenda’s life. When she had seen the advertisement in the newsagent’s shop she had told her it was just the sort of job they needed, even if it paid badly, seeing they could save on tube fares and lunches and wouldn’t have to wear their good clothes. Brenda said she’d got no good clothes, which was the truth. Freda had given up her job as a cashier in a nightclub: the hours weretoo erratic and it meant she could never get up early enough to go for auditions. Every Thursday she bought a copy of The Stage and every Friday night she went to a theatrical pub and met people in the business. Nothing ever came of it. Brenda didn’t do anything, apart from a little shopping. She got a postal order from her father every week, but it wasn’t enough to live on.

‘It’s not right,’ Freda told her. ‘At your age you’ve got to think of the future.’

Brenda, who was thirty-two, was frightened at the implication: she felt she had one foot in the grave. They had gone once to a bureau on the High Street and said they were looking for temporary work in an office. They lied about their speed and things, but the woman behind the desk wasn’t encouraging. Secretly Freda thought it was because Brenda looked such a fright – she had toothache that morning and her jaw was swollen. Brenda thought it was because Freda wore her purple cloak and kept flipping ash on the carpet. Freda said they needed to do something more basic, something that brought them into contact with the ordinary people, the workers.

‘But a bottle factory,’ protested Brenda, who did not have the same needs as her friend.

Patiently Freda explained that it wasn’t a bottle factory, it was a wine factory – that they would be working alongside simple peasants who had culture and tradition behind them. Brenda hinted she didn’t like foreigners – she found them difficult to get on with. Freda said it proved how puny a person she was, in mind and in body.

‘You’re bigoted,’ she cried. ‘And you don’t eat enough.’

To which Brenda did not reply. She looked and kept silent, watching Freda’s smooth white face and the shining feather of yellow hair that swung to the curve of her jaw. She had large blue eyes with curved lashes, a gentle rosy mouth, a nose perfectly formed. She was five foot ten in height, twenty-six years old, and she weighed sixteen stone. All her life she had cherished the hope that one day she would become part of a community, a family. She wanted to be adored and protected, she wanted to be called ‘little one’.

‘Maybe today,’ Freda said, ‘Vittorio will ask me out for a drink.’ She looked at Brenda who was lying down exhausted on the big double bed. ‘You look terrible. I’ve told you, you should take Vitamin B.’

‘I don’t hold with vitamins. I’m just tired.’

‘It’s your own fault. You should make the bloody bed properly and get a good night’s kip.’

Brenda had fashioned a bolster to put down the middle of the bed and a row of books to ensure that they lay less intimately at night. Freda complained that the books were uncomfortable – but then she had never been married. At night when they prepared for bed Freda removed all her clothes and lay like a great fretful baby, majestically dimpled and curved. Brenda wore her pyjamas and her underwear and a tweed coat – that was the difference between them. Brenda said it was on account of nearly being frozen to death in Ramsbottom, but it wasn’t really that. Above the bed Freda had hung a photograph of an old man sitting on a stool with a stern expression on his face. She said it was her grandfather, but it wasn’t. Brenda had secretly scratched her initials on the leg of the chair nearest the window, just to prove this one was hers when the other fell apart due to Freda’s impressive weight. The cooker was on the first floor, and there was a bathroom up a flight of stairs and a window on the landing bordered with little panes of stained glass. Freda thought it was beautiful. When she chose, the washing on the line, the fragments of tree and brick, were tinted pink and gold. Brenda, avoiding the coloured squares, saw only a back yard grey with soot and a stunted rambling rose that never bloomed sprawled against the crumbling surface of the wall. She felt it was unwise to see things as other than they were. For this reason she disliked the lampshade that hung in the centre of the room: when the wind blew through the gaps in the large double windows, the shade twisted in the draught, the fringing of brown silk spun round and shadows ran across the floor. She kept thinking it was mice.

‘Get up,’ said Freda curtly. ‘I want to smooth the bed.’

It was awkward with all those books sticking up under the blankets. Freda was very houseproud, always polishing and dusting and dragging the hoover up and down the carpet, and she made some terrible dents in the paintwork of the skirting board. She only bothered in case Vittorio suddenly asked to accompany her home. He wasted some part of every afternoon chatting to her at her bench, all about his castle in Italy and his wealthy connections. She told him he had a chip on his shoulder, forever going on about money and position – she called him a ‘Bloody Eyetie’. They had quite violent arguments and a lot of the time he spoke to her harshly, but she took it as a good sign, as love was very close to hate. She’d made Brenda promise to go straight out and walk round the streets if ever he looked like coming home with them. Only yesterday he had given her three plums in a paper bag as a present, and she’d kept the stones and put them in her jewel case in the wardrobe.

She told Brenda to carry the milk bottles downstairs. In the hall she paused and ran back upstairs to check the sheets were fairly clean, just in case.

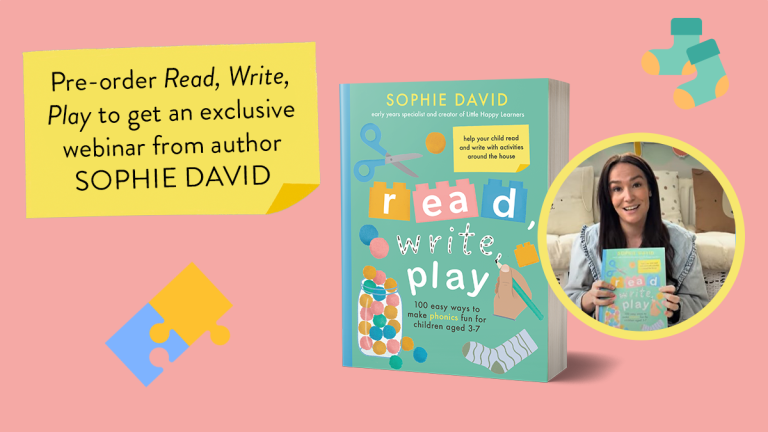

Discover the book: