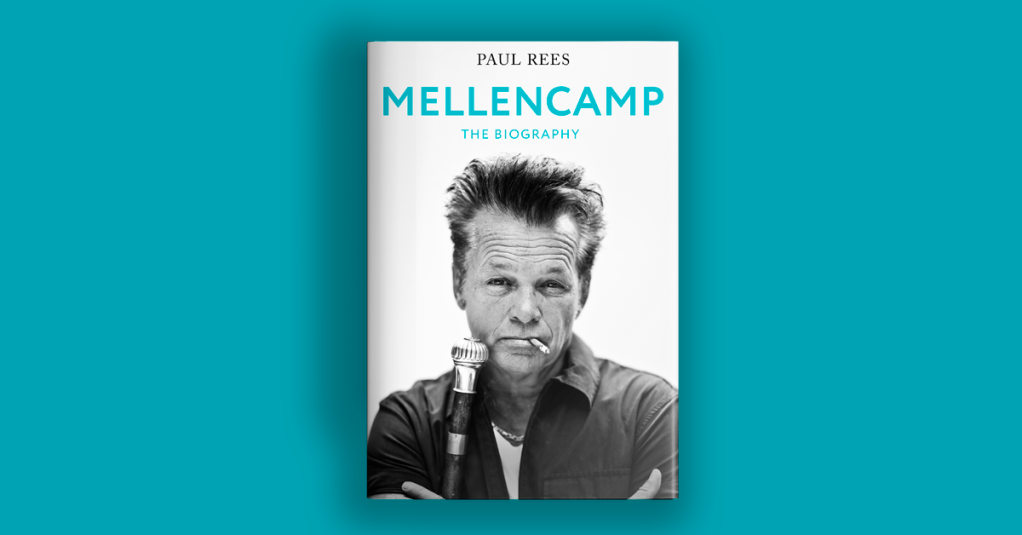

Read an extract of MELLENCAMP by Paul Rees

PROLOGUE

Three years ago, Larry McDonald had himself a crazy notion. A spry, soft-spoken sixty-nine-year-old, by nature, Larry was a steadfast, dependable sort of guy, not so much of a dreamer. Not someone who typically had flights of fancy. About the only cockamamie-sounding thing he’d done till then was open up a music store in his small, midwestern American hometown of Seymour, Indiana, population all of 17,503. He was already in his fifties by then, and likely, not one of his friends or neighbors would’ve bet a hill of beans on him making a go of it. Well, here This Old Guitar Music Store still was at 106 West 2nd Street. And now its proprietor was fixed upon having a thirty-five-foot-high mural painted over one side of the two-story, red-brick building. Furthermore, it was to be a giant portrait of Larry’s old high school buddy and one-time bandmate.

Back in the midsixties and as all over America, Seymour witnessed a genuine pop-culture eruption. The town was suddenly rife with callow, virgin beat groups. Most all of them striving to look and sound just like a bunch of mop-topped Brits, The Beatles. Rocksteady Larry was drummer for a bunch of them, since they broke up just as fast as they were formed. They played backyard barbecues and the occasional junior high dance.

Often as not, stationed center-stage in front of Larry would be a cockier, surlier kid. He had dark, blazing eyes and a mouth on him. Sang and played guitar, spitting out the words, hacking away at his instrument, as if he were in a fight with himself and the whole rest of the world. No one had called him it just yet, at least not officially, but no doubt, sixteen-year-old John Mellencamp was a little bastard.

Upon leaving high school, Larry married his sweetheart, packed away his drum kit, and settled down to raise and provide for a family in Seymour.

That much he’d managed about as well as a man could by the time he decided to put his money into the music store. The building This Old Guitar Music Store occupies was once Baldwin’s Drug Store, where a generation of local kids, Larry and John among them, went to hang out, drink cherry colas, and slip out back for a sly cigarette. The store is next door to a Mexican takeout and the STEPS Dance Center. A block up the road, West Street is bisected by Seymour’s main drag, Chestnut Street. Down the adjacent East Street, the store looks out to a parking lot and, across Indianapolis Avenue, to the town’s railway tracks.

Before he was even out of school, John got hitched to his girlfriend, who was three years older than him and pregnant already. As a matter of fact, the two of them eloped across the state line to Louisville. Not that he intended on being tied down to Seymour, no sir. Out of all the kids he played with in all those long-ago bands, Larry said, it was John, and John alone, who had something intangible, something else that made him stand apart. Whatever the odds, and coming from Seymour, the veritable back of beyond, they surely were long and great, he’d got himself wings to fly high and far. Though didn’t he just fly higher and further than anyone could’ve ever foreseen, most likely including John himself.

—–

From his first day of business, Larry put up photographs around the store of the two of them in their high school band days. People would troop in just to ask if he really did know John Mellencamp, and might he be able to have John donate something to a good cause. The two of them kept in touch, too, and John was always obliging. Once a month or so, Larry would send him a guitar to sign to be auctioned off for a local charity. It got Larry to thinking it was past time Seymour itself paid tribute to its now-famous son.

He approached John with his idea. John signed off on it directly. Next Larry took it to another one-time high school classmate, Jana Plump, now an administrative assistant at City Hall. Plump passed it on to Seymour’s mayor, Craig Luedeman, who presented it to the Seymour Redevelopment Commission, which agreed to fund Larry’s proposal to the tune of $25,106. This was October 2018. Progress was delayed for a year when Larry’s building was damaged by fire. The following October, Seymour City Council commissioned an Indianapolis-based artist, Pamela Bliss, to paint McDonald his mural. “I kind of grew up with John Mellencamp’s music,” Bliss told a local TV station, WLKY. “So, it’s quite an honor.”

Bliss, working with a masonry crew of four and assisted by volunteer helpers, including the first-grade class taught at Redding Elementary

School by John’s younger sister, Janet Mellencamp Kiel, took six weeks to complete the project. The finished work pictures two Johns, set on either end of the wall. In one, a half-length image of him as a young man, he’s painted with his back to the viewer. He is sporting a denim jacket with the words “Seymour, Indiana” emblazoned across the back. The other is full-length, an image of him as an older man, not so awkward looking, somewhat more dignified. In this, he’s attired in a sober black jacket and clasps an acoustic guitar. Still with those dark, hooded eyes that seem to convey degrees of hurt, pride, mystery, menace, and a deep inner strength.

John attended the official unveiling of the mural on a gray December day, posed for yet more photographs along with Mayor Luedeman. He signed his initials, “JJM,” on the wall in black paint, returned in triumph to the town in which he was born and made.

This was the same John Mellencamp who fought and scrapped his way out of Seymour and got written off by one rock critic after another

as a no-hoper. He proved them all wrong by force of will and with a near-pathological drive to better himself, until he stood on the shoulders of giants. Though to Larry McDonald, he wasn’t so much different from the balled-up punk he’d once played behind. “Slowed down a little because of our age,” said Larry. “But a good friend, a good buddy still.”

—-

One has to visit with John in Indiana to better appreciate both the scale of his accomplishment and the depth of his roots. First, to the one-store-and-a-church township of Belmont, forty-five minutes’ drive northwest of Seymour. Surrounded by the verdant expanse of the Yellowwood State Forest and the Brown County State Park, here is where Mellencamp has made the great bulk of his music the past thirty-five years.

Comprised of two green-painted clapboard buildings, doglegged around a pebbled courtyard, Belmont Mall has operated as John’s recording studio and rehearsal space since 1985. From the outside, it’s just as rustic-looking and weather-beaten as the other handful of structures that huddle along State Road 46. A basketball hoop hangs from one wall. Below it, off to one side, is a small, makeshift sign informing visitors one particular parking space is “Reserved for Elvis Presley.”

Inside, the walls are lined with gold and platinum discs, framed citations, and commendations. One marks John’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2008. Another is his 2012 John Steinbeck Award.

There’s a handwritten note of appreciation from Barack and Michelle Obama, and black-and-white portraits of Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash. A black-and-white portrait of James Dean, the doomed rebel born two hours north of here in Marion, Indiana, hangs in the toilet. The studio and rehearsal rooms are neat, clean, and painted white. Master tapes of all the songs and records put down at Belmont fill another room. They are labeled in black ink: “Pink Houses,” “Small Town,” and “Paper In Fire”; Uh-Huh, Scarecrow, The Lonesome Jubilee, and more.

John keeps a loft apartment in Manhattan and a holiday house on Daufuskie Island, South Carolina, but his main home is five miles out of Belmont, heading east along the 46 toward Bloomington. It’s an imposing, ranch-style house of heavy stone, dark wood, and glass, set at the end of a dirt track that winds and bumps through sixty-three acres of forest. Set right out on the shore of Lake Monroe’s vast body of water. Most days, the only sounds to be heard from the outside pool deck are the splashes of paddle boats, or the squawking of hawks, circling above in a cloudless, blue sky.

A couple of miles back up the dirt track, navigated by John at teeth-rattling speed in a small, green John Deere Jeep, there is his art studio. He’s painted all his life, seriously since the mid-1980s. Made of corrugated steel, sparkling under the midmorning sun, it rises from a woodland glade like a barn out of science fiction. The interior is made up of more dark wood: the floor, high beams, and pieces of antique furniture.

Floor to ceiling windows frame a green and gold vista of walnut, sycamore, and witch hazel trees. Hefty art tomes and faded photographs of four generations of Mellencamps occupy a glass-fronted cabinet. Tucked away in a corner are an acoustic guitar and a vintage amplifier. All around are Mellencamp’s canvases, propped against walls or standing on easels, next to work surfaces crammed with paints and brushes. His portraits are rendered in heavy, brooding colors. Dark reds, browns, and blacks, the faces pictured seeming proud, defiant, enraged, or haunted. Powerful pieces, they are best described by New York Times art critic David L. Shirey as “searchers for souls . . . stark, shattering face-to-face with who we really are.”

Sitting at a long wooden table, John lights up the first of a chain of cigarettes. One, two puffs and he’s shaken by a hacking, graveyard cough. He’s short, but solid; bullish; arms thick as slabs of meat. His black-goinggray hair is swept up into a pompadour. Those black, black eyes peer back at you, wreathed in smoke, unwavering. He takes his time to consider the question of his near-seventy years on Earth, and a professional career enduring a half-century and counting. Of what it has meant to him and adds up to. When he at last answers, it’s quietly, ruminatively, and in a burned husk of a voice. “Listen, man, I have to tell you, I’ve been so fortunate,” he says.

“I’ve met everybody in the world I ever admired. I’ve worked with Bob Dylan and Stephen King. I’ve worked with Larry McMurtry. I speak to Joanne Woodward on the phone, every day. When her old man Newman died, I just started talking to her; she and I’ve become tremendous friends.

“A lot of my kids are like, ‘Dad, get out of Indiana.’ They tell me, ‘We don’t want to come to Indiana. You should fucking move.’ Sometimes I question myself about it, too. But no, I’m not going to move. See, I’m very lucky. I live here, but I’m never here. I’m always here, there, and everywhere, but I come back to here. I could probably have been more successful if I’d left here, but I didn’t really get into it for the money. I never really thought about being successful. Well, I thought about it, but it wasn’t the main issue. If it was, I wouldn’t have had a couple of the managers I’ve had.

“I like being the underdog. I’m like Sisyphus. I like rolling the rock up the hill. Regrets? Yeah—tons of ’em. So many things I wish I hadn’t done and said to people. I’m not proud of being as difficult as I’ve been. Some people didn’t deserve it. Some people had it coming. Some people I’ll never forgive. There’s no excuse for deliberately being cruel to somebody, or deliberately stealing from somebody and knowing you’re doing it. But I wouldn’t trade what I’ve done for anybody. Because I’ve been right to the top and there ain’t nothing up there worth having. I found it all to be fucking stupid. And I’m having more fun now than I ever did back then.”