Read an extract from The Halfpenny Girls by Maggie Mason

ONE

Marg

1937

‘Oh, Alice!’ Marg’s heart filled with pity as Alice came towards her. One of Alice’s eyes was swollen and her cheek looked bruised.

Before Marg could react further, Edith stepped out of her house across the road at the top end of Whittaker Avenue, in Blackpool – a street lined with terraced houses with their

living room doors leading straight onto the pavement. Edith called a greeting as she ran over to them, just as Alice reached Marg.

Another day working in the packing department of Bradshaw’s biscuit factory loomed for them, but though the work was repetitive and back-breaking, their hours of labour were some of their happiest. Released from their cares at home and all that weighed them down, they enjoyed the banter that went back and forth amongst the women they worked alongside. Marg linked in arms with Alice and Edith. Friends since babyhood, they’d been born on this street within days of each other and would celebrate their twentieth birthdays this September.

Alice, the shortest of the three, had a dainty figure, a mound of blonde curls framing her pretty face, and huge liquid-blue eyes that were the first thing everyone noticed. Though her looks were often spoilt by a black eye or bruised cheek – even a split lip on one occasion. Edith, the tallest by an inch, had strong, beautiful features and hazel, expressive eyes, which gave her a striking presence. Her jet-black hair added to this as she wore it rolled off her face and falling in waves down her back. Beside them, Marg felt the least attractive, with her face dotted with freckles and her mousy-coloured hair that had a mind of its own – more prone to frizz than curls, and sometimes untameable.

Sighing, Marg leant towards Alice and asked the question that she had no need to. ‘Your da?’

Alice nodded and a tear plopped onto her cheek.

Snuggling her in closer, Marg felt the pity of Alice’s life. Her da was changed beyond recognition from the jolly man Marg remembered as a kid. He’d always had time for them. If

they were playing in the street, he’d pick them up in turn and twirl them round with his hands held high, making them scream with a mixture of laughter and fear at being dropped – which he sometimes pretended to do.

Then a fateful day five years ago changed him: an accident in the rock factory where he worked left him in a coma for months. Unbeknown to him, his beloved wife, and ma to

Alice and her three younger brothers, fell ill with cancer. She had passed away by the time Alice’s da came to. This saw the dawning of a change in him: the fun-loving man was no more and the anger that seemed to constantly burn in him erupted over the slightest provocation.

Marg felt at a loss as to what to say to Alice, but was saved from worrying about it as a cry from her own front door had her turning her head to see her gran standing on their step. Running back to her, she took her hands.

‘I’m hungry, Marg.’

‘Stay inside, Gran. You’ve had your breakfast. Porridge, remember? I made you a nice bowlful and you ate the lot.’

‘Did I, lass?’

‘You did, Gran. Now, go inside.’

‘I tried to calm her, Marg.’

‘I know, Jackie.’ Marg’s adored younger sister appeared at the open door.

Marg smiled. ‘It’s all right, lass. Have you got everything you need ready for school?’

‘Aye, I’m ready. And I’ve washed the pots. Gran was asleep in front of the fire while I did them.’

‘Is Ma not up yet, lass?’

‘Naw, I took her a mug of tea up. She looks awful, Marg.’

Jackie’s expression held despair.

‘Look, lass, you’re not to worry. I’ll sort it. I’ll ask Ada Arkwright to look after Ma and Gran for the day. I’ve got a bit extra coming in this week from the overtime I did on Saturday. It’ll be enough to pay her. You’re not to concern yourself. You just concentrate on getting that school certificate – that’s the most important thing in your life, Jackie. You leave the worrying to me, eh?’

‘I can chip in, Marg. Mr Fairweather gave me a bit extra for staying on last night and helping him to pack all the grocery boxes for his round today.’

‘That’s good, as I had earmarked some of my overtime money for paying your tutor – I owe him two weeks as it is.’

Marg’s one ambition in life was to give Jackie a good start. She’d never known a cleverer kid. And no matter what it took, she was determined that Jackie would make something of herself and not end up in a dead-end job like herself. To ensure her sister got her school certificate with honours – something she would need to be considered for college – Marg had approached her old headmaster, Mr Grimshaw, and asked him to give Jackie extra lessons after school. He’d agreed to tutor her two evenings for two shillings a week. This was a lot to find out of her average weekly pay of thirty-two shillings. After that and the twelve shillings for rent, ten shillings for food, five for a bag of coal, which she bought every week, stockpiling in the summer to cover the bitter cold of the winter, she only had a few bob left to feed the gas meter. The rest went to the tally man, to buying the books Jackie needed and to paying for help to look after her ma and her gran, who’d lost her marbles.

Like most others around here, they couldn’t afford the doctor often and relied on Ada Arkwright’s services for anything medical. A Red Cross worker during the Great War,

she delivered all the babies in the area and saw to most folk’s ailments for a quarter of what the doctor charged, often accepting a favour for payment, such as knitting her a new cardigan. But Marg had no favours to offer, and so had to find the two shillings she charged for a day’s care.

‘Marg! Come on, lass. We’re going to be late!’

‘Sorry, Edith, you two go on. Clock me in, will you? I’ll not be a moment. I’ll knock on the side door so listen out for me and make sure that Moaning Minnie don’t notice anything. Mind, she’s always too busy making eyes at the boss.’

Edith laughed at this as she turned away, taking Alice’s arm. But for all her bravado, Marg’s heart dropped to see her two friends carry on on their way to work without her, and though she’d made a joke, she really didn’t want to get on the wrong side of Mrs Roberts, the floor manager, known behind her back as Moaning Minnie. Sixty if she was a day, Moaning Minnie painted her face like a youngster experimenting with make-up. Eyes heavy with bright blue shadow, ashes clogged with mascara, and her bleached blonde hair frizzed to rival Marg’s. She was a tartar to them, docking them a full half hour for being just a few minutes late, and lording over them, picking up on the minutest of mistakes that would get through but for her beady eye. Then bawling out the culprit and making them repack the whole tin. This meant a setback if you were on piece work.

Shaking these thoughts off , Marg concentrated on helping Gran. ‘Eeh, love, let’s get you settled back by the fire.’

‘I’ll find you a biscuit, Gran, how would that be?’

‘No, ta, Jackie, love. I’ve had me breakfast. Marg made me some porridge, didn’t you, Marg?’

‘I did, Gran.’ Marg smiled at Jackie. ‘Pop along to Ada’s, lass, ask her to come as soon as she can, eh?’

As Marg tucked a blanket around Gran’s knees, it seemed to her that her troubles were piled high, and coping with everything was weighing her down. Gran had been this way for over a year now, not knowing from one minute to the next what was happening, and it felt as though they were losing a piece of her each day. She’d moved in with them when their da had died six years earlier. A lovely da, who Marg still grieved for. He’d had a weak heart, then one day he just keeled over and was gone. Her ma had never been the same since. Always ailing, she suffered with her breathing, and often had days when she was so weak she couldn’t get out of bed.

These times escalated Marg’s problems as she just had to go to work. The only alternative was to fall back on the meagre parish relief, and she didn’t want to do that. As it was, she ended up borrowing from her uncle more often than she wanted to and more than she could pay back. Her da’s brother, Uncle Eric, was nothing like her da had been. The local money lender, bookmaker and pawnbroker, Eric went from house to house collecting his debts, or some item of value that he’d hold until the borrower could pay – or sell off if they couldn’t. He’d jot down everything Marg borrowed, licking the tip of his pencil before writing in his grubby little book. But then sometimes, out of the blue, he would let her off her payments, saying, ‘Your slate’s clean, till the next time.’ Then he’d smile a funny smile and say, ‘Your uncle’s always here for you, you know that, Marg.’

Marg had mixed feelings about her uncle. Mostly, she didn’t like him, though she couldn’t have said why – apart from his bullying ways with folk who couldn’t pay, and his preying on the poor, he always treated her with respect and spoke kindly to her. It rankled her that he wasn’t like that with Jackie. He wasn’t unkind to her, but, well, indifferent is how she’d describe his attitude where Jackie was concerned.

With Gran settled, Marg was about to leave when the sound of her ma knocking on her bedroom floor made her dash upstairs.

‘Ma, Ma, are you all right?’

Ma dropped the old walking stick she kept by her bed and looked up at Marg. The sound of her ma wheezing and the sight of her leaning over the side of the bed hurt Marg’s heart. ‘Ma? Eeh, Ma . . . Don’t worry, Ada’ll be here in a mo. She’ll help you. She always gets you going again with a bowl of hot water and Friars’ Balsam, don’t she?’

Lifting her ma’s frail, thin body, Marg held her gently in her arms. Fear trembled through her at the feel of Ma’s struggle to draw her breath in. ‘You’ll be all right, Ma. Try to calm down and breathe slowly. That’s it. By, you’ve been right for days. I thought you were having a good patch.’

‘I – I was, lass. Don’t . . . worry about me. Get – get off to work.’

‘All right, Ma.’ Propping her up against the mound of pillows, she kissed her sweat-soaked forehead. ‘I love you, Ma. We’ll get through, I promise. There’s a bit of overtime going at the factory and not many want to do it. I’ve asked for as much of it as they can give me.’

‘You’re . . . a good lass.’

‘I wish I could do more, Ma. Anyroad, I’ve got to get going. I’ve got the tea all ready for tonight: I’ve peeled the spuds and put them in a saucepan of water and I’ve got a casserole on low in the oven. It’ll take all day so don’t worry about it. I’ll soon get everything going when I get in. Oh, and there’s a couple of hard-boiled eggs in a dish on the cold slab. You and Gran can have them for your dinner with some doorsteps off that loaf that’s left, and there’s a nice bit of dripping an’ all. Make you both a sandwich, eh?’

‘Ta, love. Now, off you go. You’ll be getting the – the sack.’

Hugging her ma once more, Marg skipped down the stairs. Ada met her as she got to the bottom. ‘Now, Margaret, this shows you that what I’ve always said is right.’

Ada always used her full name when she was on what she called ‘official business’. It was a name Marg loved as it was her da’s mother’s name, and she’d loved her Granny

Margaret.

‘You’re going to have to put your gran in an asylum, lass, and think about sending your ma to a sanatorium – both would be better off . You know that this can’t go on. I can’t always come to your aid. I’ve got Mrs Coop about to drop her fourth nipper and Mr Herald on his last legs. I’ll have to go if I’m fetched to either of them.’

‘I know, Ada. Get Ma on her feet and she’ll cope with Gran. But neither of them are leaving this house until they have to – God, I hope the day never comes. But no matter what, I couldn’t put them away. I couldn’t.’

‘Well, you get yourself to work, lass. Your gran looks peaceful there. Look, she’s snoring, bless her. I’ll see to your ma first.’

‘Ta, Ada. I’ll pay you at the end of the week.’

Hugging Jackie before she left and telling her not to be late for school, Marg took off and ran all the way to the factory on Mansfield Road, a three-minute sprint instead of her usual five-minute walk. Her first tap had Edith opening the door. Marg sidled in.

‘Moaning Minnie’s been on the prowl, Marg. I told her you were in the loo, so hurry yourself.’

‘I will, ta, lass. I’ll nip into the cloakroom and leave me jacket. You get back to the line.’

The line referred to the women picking the biscuits as they came down the conveyor belt. Today, they were packing fancy biscuit barrels that would be on the shelves for Christmas – the snow scene they depicted was at odds with this being July. Each tin had to contain four custard creams, which were placed inside the corrugated paper that was shaped into pockets. Once they’d done this, the tins would go to the next belt to be packed with chocolate digestives, then on again to have rich tea added and, finally, shortbread biscuits.

As Marg took her place next to Edith’s side, Edith grinned.

‘Eeh, Marg, you’re like a cat with nine lives, but you must be coming to the end of them soon. Moaning Minnie’s on to you, I’m sure of it.’

‘I know, and I worry about you and Alice – if you’re caught clocking in for me, you could get the sack too. Oh, I don’t know, life’s so complicated.’

‘Maybe you should listen to what Ada’s always telling you?’

‘No, never. Gran stays with me. Anyroad, I’m hoping she won’t play up in the mornings again. You just never know with her. I’ll nip home during dinner break and make sure

they’re both all right.’

When at last one o’clock came, Marg scooted out of the factory gate. She’d no time to eat the oven-bottom bun that had been part of a batch she’d baked over the weekend, but she didn’t care. She just needed to put her mind at rest. It was as she was about to cross Talbot Road that she met Betty, Edith’s mum, and felt a sense of dread wash over her as Betty called out in a slurred voice, ‘Hel-yo, lash.’

Marg groaned. A known drunk, Betty was the last person Marg needed to see, even though the encounter made her troubles seem like nothing to what Edith, and Alice too, had

to put up with.

‘Hello, Betty, love. I can’t stop, I’ve only got a short time to get to me ma and gran.’

‘Have you got a couple of bob to shpare, Marg, lass? I’m dying for a fag.’

As Betty wobbled towards her, her sour, alcohol-fuelled breath wafted over Marg.

‘No . . . where will I get a couple of bob from, eh? Anyroad, you only need fivepence to get five fags, and if you’re thinking of another drink, you’ve had enough, Betty. See you later, love.’

‘I’ll jush have to sell me body then, won’t I?’ Betty shouted as Marg carried on making her way home.

Marg wanted to shout back that no one would pay for her body the state it was in, but she just laughed and ran on her way.

The laugh didn’t touch her inner self, though, as she thought of how mortified Edith was when her ma got like this, and how it usually meant that she had to go around the

town paying folk back for what her ma had borrowed. Marg had told her time and again not to because knowing Edith would pay, the locals never refused Betty credit, but Edith

needed to keep her pride – well, as much as she was able to with a ma like Betty.

When Marg turned into her street, the sight of her gran sitting outside on a kitchen chair cheered her. ‘Hello, Gran. Enjoying the sunshine, eh?’

‘Do you know me, lass?’

‘Aye, I know you. You’re a lovely lady who I love very much.’

‘Oh?’

‘It’s Marg, Gran.’

‘Our Marg?’

‘Aye, the very one.’

‘Why didn’t you say so? Hello, Marg. Were you a good lass at school today?’

Marg sighed. ‘I was, Gran, but I’ve to get back there before the whistle goes. Is Ma about?’

‘Me ma? Where?’

‘Never mind, Gran. You go back to your daydreaming.’

As Marg stepped inside, her ma greeted her: ‘Marg! Hello, lass, I didn’t expect you home.’

‘Are you all right, Ma?’

‘Aye, Ada got me going again, ta, lass, but you shouldn’t have left work.’

A whiff of stale tobacco gave Marg a feeling of despair. ‘Ma! You’ve been smoking! How did you get a fag? Who gave it to you?’

‘Oh, don’t take on, Marg. I told you, it clears me lungs. It really helps me. I need me fags.’

‘But how did you get them?’

‘Your Uncle Eric called round. He brought me a packet.’

A voice from outside shouted, ‘That’s not all he brought her, I heard . . .’

‘You shut up with your silly waffle!’

Ma had gone red in the face at Gran calling this out, but she laughed a nervous laugh. ‘Me ma can be a silly old cow with her sayings. She’s just not your old gran anymore, is she? Anyroad, lass, get back to the factory afore you lose your job.’

Just before Marg left, she asked how long Ada had stayed.

Once again, Gran piped up: ‘She left when that uncle of yours came, and I’ve been out here since – I want to come in, Marg.’

‘I’ll get her in. You get going. Go on, lass.’

As Marg went, she heard her ma telling Gran off in a joking way. ‘You don’t miss much for all your brain’s addled, Ma. Come on, let’s get you inside and out of trouble.’

Her gran’s reply shocked Marg: ‘Well, having fun and games with that Eric – it’ll get you nowhere, you know. That kind only take, they never give, you mark my words.’

Though Marg tried to shake it off , the feeling that her gran had planted in her head wouldn’t leave her all afternoon.

No, Ma wouldn’t . . . would she?

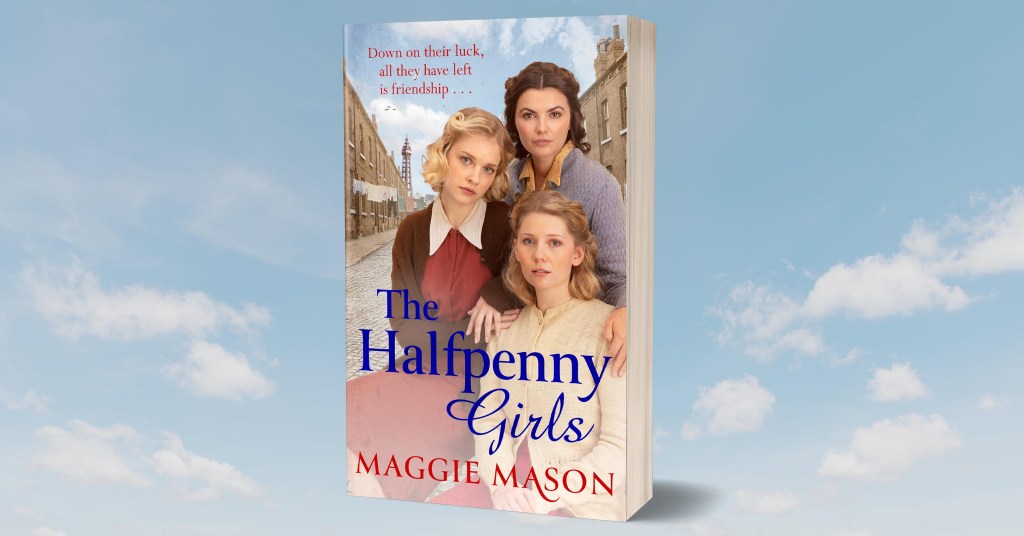

THE BRAND NEW SAGA SERIES BY MAGGIE MASON - MEET THE HALFPENNY GIRLS. . .

'In the grand tradition of sagas set down by the late and great Catherine Cookson ' Jean Fullerton on Blackpool Lass

Down on their luck, all the have left is friendship . . .

It is 1937 and Alice, Edith and Marg continue to face hardships every day, growing up on one of the poorest streets in Blackpool. Penniless, their friendship has helped them survive this far, but it'll take more than that to see them through the dark days that lie ahead . . .

Alice is coping with a violent father and the weight of the duty she carries to support her family, Marg is left reeling after a dark secret about her birth comes to light and threatens to destroy the life she knows, and Edith is fighting to protect her alcoholic mother from the shame of their neighbours and keep her brother on the straight and narrow.

A chance encounter at the Blackpool Tower Ballroom promises to set their lives on a new path, one filled with love and safety and hope for a brighter future. Will The Halfpenny Girls, who have never known anything but poverty, finally find happiness? And if they do, will it come at a price?

The first in a brand new series from reader favourite Maggie Mason, The Halfpenny Girls is the perfect heart-warming family saga about overcoming hardship and the value of friendship. Perfect for fans of Val Wood, Kitty Neale and Rosie Goodwin.

Readers LOVE Maggie Mason's Blackpool sagas:

'5 stars - I wish I could give it more. Wonderful read.'

'Another must read book'

'What a brilliant book. I couldn't put it down!'

'I was hooked from the first page . . . this author is a must read'

'A totally absorbing read'