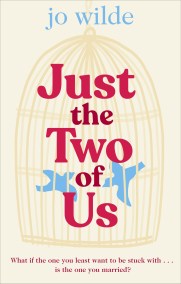

Just the Two of Us Extract

Chapter One

Day One

Julie Marshall stepped out of the shiny offices and glanced fur- tively up and down the busy street. The brown envelope seemed to burn her fingers and she shoved it hastily into her shoulder bag, grateful that she’d thought to bring the big zebra-patterned one she knew Michael hated. It seemed apt. Once she’d handed the papers over, it wouldn’t matter what Michael hated. She’d be free to do and live and be however she wished.

‘Free!’ she said out loud, trying to convince herself. A passing couple looked at her askance. They were young and handsome and their fingers were interlaced with tight confidence. ‘Don’t worry,’ she threw at them. ‘I’m not drunk, just getting divorced.’ They scurried away, pulling even closer together as if she was some sort of curse they needed to ward off. Maybe she was. ‘Free,’ she said again, quieter this time, but it still didn’t sound right. It still didn’t fight off the other words struggling to batter

their way out of her head: alone, useless, failure.

She shivered and turned determinedly towards the car park. It wasn’t a failure to end her marriage. It took strength to admit a relationship wasn’t working any more, or so everyone said. The problem was, she didn’t feel strong. She was doing a good impression – walking strong, talking strong, acting strong – but underneath she felt as stable as a vodka jelly.

Earlier, when she’d gone into the estate agent’s to pick up details of flats for rent, she’d been so shaky she’d dropped half the leaflets. The young man had looked at her with such concern that she’d blurted out that her daughter had had a nasty break- up. She’d been instantly ashamed of the lie but she was even more ashamed of the truth – that somehow, without noticing, she’d slid from having the sort of marriage she’d smugly known other people envied to the sort that, well, that wasn’t really a marriage at all.

She blinked ferociously. She wasn’t going to cry. She wasn’t going to go back to the dark days. No way. She’d dragged herself out of that mire and she owed it to herself to stay out of it. She still had things to do with her life and she wasn’t going to let some idea of failure hold her back. People divorced every day and felt better for it. Her own sister had been like a different person when she’d emerged from her marriage ten years ago, hadn’t she?

Julie pushed thoughts of Clare aside. Her little sister spent her days lurching from one unsuitable relationship to the next, but that wasn’t how Julie was going to do it. She wasn’t leaving this man to find another, but to find herself. She groaned at the cliché and fumbled in her bag for the plastic ticket that would let her into the impossibly secure car park. The envelope was in the way and she pushed it impatiently aside as she scrabbled amongst the more usual detritus for the ticket. Her fingers brushed the fluffy ball of a key ring that Adam had given her for Christmas last year – ‘Let’s see you lose this, Mum’ – and her heart jud- dered. She hoped the kids wouldn’t be too upset.

They’re not kids, Julie, she reminded herself. The girls had long since left home, and, with Adam in his fourth and final year at university, he might as well have done. They were grown-ups with their own lives now and she couldn’t stay miserable just for the pretence of a happy home.

Again the tears threatened. Again she pushed them back behind her eyelids. She hated that her marriage had turned to dust, but she no longer had any idea how to hold it together. These days she and Michael shared little more than a front door. They slept in different rooms and managed to keep themselves so busy in their jobs and separate social lives that they could go days without actually seeing each other.

Julie couldn’t remember the last time they’d had a proper conversation, one that went beyond informing the other that they’d taken the bins out or that dinner was in the fridge. They cooked for each other but rarely ate together. They took the clothes off the washing line but never off each other’s bodies. They didn’t even bloody argue any more. She’d tried to fix things over the last few years – she really had – but she’d accepted now that their marriage was beyond repair. And with their thirty-fifth anniversary just a month away, she had to do something. Celebrating a dead marriage would be nothing more than a farce, and it was time to face up to that. Divorce was for the best.

But that didn’t mean it wasn’t sad.

Her fingers closed gratefully around the plastic ticket and she pressed it to the door pad. Nothing. The big grey door stayed resolutely shut. She turned it over, pressed it again. Still nothing. ‘Please let me in,’ she begged. The door paid no attention. For the third time that afternoon, Julie blinked back tears.

‘Pain in the arse, aren’t they?’ a cheerful voice said, and she turned to see an older woman bustling up behind her. ‘Just a minute.’ She dumped handfuls of shopping bags on the floor, gesturing self-consciously to them as she dug for her own ticket. ‘Supplies. In case we go into whaddyacallit – lockdown.’

‘Lockdown?’ Julie asked. ‘It won’t come to that, surely?’

The woman gave her a sideways look. ‘Where’ve you been, dear?’

With a divorce lawyer, Julie wanted to say, but the woman was far too smiley to be hit with that sort of unpleasant detail. She felt foolish suddenly – the world was going mad and she was fretting about one little marriage. But it was her marriage, or it had been, and right now it felt all-consuming.

She looked down at the woman’s bags, spotting toilet roll, a multipack of custard creams and a large bottle of Baileys.

‘That’s in case we run out of milk,’ her new friend said, bending and patting the liqueur as she might a small dog. ‘It’s lovely on cornflakes. Now, here we go!’

She pulled a ticket from her bag and held it up to the pad.

The door sprung obligingly open. ‘How did you do that?’ Julie asked.

‘Magic!’ The woman smiled and waved Julie ahead of her as she gathered up her shopping. ‘Did you validate your ticket when you arrived?’

Julie groaned. ‘Probably not. I’m hopeless at things like that. My husband’s always saying . . . ’ She stopped. My husband! For thirty-four years she’d had a husband. Soon it would just be her.

‘Are you OK?’ The woman was looking at her in concern, and Julie realised she’d stopped dead halfway up the concrete stairs.

‘How will I get out?’ she asked, feeling ridiculously shaky again.

‘Go to the office, dear; they’ll soon sort it.’

Julie smiled her thanks and stumbled in the direction indicated, but her thoughts were back at the shiny lawyer’s offices, and she clutched her zebra-print bag and its dark contents close against her as she approached the car park attendant.

‘I wonder if you could help me?’ she asked in her politest voice. ‘I’ve messed up, I’m afraid, and I really need to get out.’

‘Course I can, love,’ the burly bloke agreed with a grin. ‘Follow me.’

Julie did as she was told, suddenly wondering if she’d actually be better off stuck in this car park than heading for home. It was one thing getting the divorce papers from the lawyers; quite another to hand them over to her husband. How on earth had it come to this?

Half an hour later, Julie pulled off the village high street and onto their quiet cul-de-sac, trepidation rising within her. In the spring sunshine her home looked far too welcoming for comfort. The cherry tree in the middle of the tiny front lawn was just starting to blossom, and the pots either side of the porch were also sending up promising green shoots. She killed the engine and sat on in the car, gazing at the place she’d called home for the last twenty years. It wasn’t anything fancy, but it certainly looked good against the blank little flats whose promises of ‘bijou living’ and ‘cleverly designed spaces’ were lurking in her bag alongside the divorce papers.

To get the space they’d needed for their growing family, they’d had to drop their dreams of a cutesy cottage in favour of a 1950s box, but Julie had rapidly grown fond of the smooth white walls and wooden bay windows. When Michael had added a pretty timber-framed porch in an early rush of energy, they’d smugly pronounced it better than any cottage, and it had certainly proved a happy home. Bright curtains hung at every window, and over the side gate you could just catch a glimpse of the large back garden that led out onto the fields beyond. With three energetic kids, all that outdoor space had been the clincher, and they’d made an offer on it twenty minutes after the first viewing. It had been one of the best decisions they’d ever made. But recently her heart had dropped every time she’d pulled onto the drive, and that couldn’t go on.

Grasping her bag, she leapt out of the car and let herself in through the front door. It was deathly silent inside; gone were the days when her home reverberated with the happy noises of family life. Michael, however, should be here. Yesterday he’d announced that his engineering company was ordering everyone to work from home, and he was going to set up office in Briony’s room. The thought of having him around all the time was what had sent her to collect the papers from the lawyer at last; now all she had to do was hand them over, pick a flat and leave. And with the government bringing in measures in response to the virus and normality starting to shut down, the sooner she did that the better.

She stepped cautiously inside, her heart beating as if she were about to go on some scary fairground ride. There was no sign of her husband in the living room or the kitchen, and it didn’t feel quite right to shout a cheery ‘hello’ as a precursor to delivering an affidavit of a goodbye. He must be up in his new office, she thought, and was turning to head for the stairs when a movement outside caught her eye.

Michael was out in the garden, bending down to feed something to Mr Nibbles, Briony’s ancient rabbit. He was chatting unselfconsciously to him and Julie watched, feeling strangely voyeuristic. Her husband was smiling, and she realised that she didn’t see that often these days. He mainly nodded or grunted or just shuffled past her. Any words they did exchange were terse and practical; gone were the days when he’d chatted to her as he was doing to the rabbit now.

Sadness pierced her and she clutched at her bag, hearing the envelope crackle under her arm as he rose and came back towards the house. She knew he’d spotted her because his body tensed up. It was sad, but it was also reality; they’d grown apart and it was pointless pretending otherwise.

‘You’re back,’ he said gruffly as he came through the door.

‘I’m back, yes.’ ‘Nice day?’ ‘Hmm.’

He edged past her, making for the stairs, and she swallowed and forced herself to speak again.

‘Actually, no, not that nice. Michael, I need to talk to you.’ He stopped, back to her. ‘Now?’

‘Ideally, yes.’

She reached into her bag and her fingers closed around the envelope. No point in dragging this out; she just had to get on with it. So why were her hands shaking? ‘It’s important,’ she stuttered.

He turned towards her with a frown and she braced herself for him to snap.

‘Are you OK, Julie?’

To her surprise, his voice was soft, kind. He’d always been kind, actually. She could remember her mum saying that when she’d first brought him home: ‘Oh, well done, love – you’ve picked a kind man. They’re very much the best sort.’ She swallowed again.

‘I’m OK. Well, actually . . . ’

She tried to take the envelope out of her bag, but it felt impossible, as if there was a Star Wars-style force around her, stopping her from delivering it to him. Ridiculous! Taking a deep breath, she pulled it out decisively just as Michael’s phone rang and he looked down.

‘It’s my boss,’ he said with an apologetic grimace. ‘I’d better take it.’

‘But . . . ’

‘Can we talk later? After the PM’s briefing maybe?’ ‘The briefing. Of course. Let’s talk after.’

He lifted the phone and cut off the bleat.

‘Geoff! How are you?’

Julie stood there, divorce papers behind her back, as he sidled apologetically off down the corridor. The rush of relief was enormous – except, of course, that it meant the deed still had to be done. Ah well. Just having the papers in the house made the decision more real, and a couple of hours to get used to that wouldn’t hurt. She slowly drew the little sheaf of property details out of her bag. Perhaps, if she chose a couple, she could set up viewings for next week.

Yes, she decided, as she heard Michael’s voice rumbling away up in Briony’s room, she’d get changed, make some dinner and settle her nerves a little. Then, after listening to whatever the PM had to say, she and Michael could talk. It was time to find a new, separate path into the future, and hard as that was, it would surely be better for both of them in the long run.

Chapter Two

Julie stared at the television, seeing the word scrolling determinedly across the bottom in shouty red script.

Lockdown.

Above it, the prime minister was speaking into the camera with careful calm about ‘essential shopping trips’ and ‘key workers’, but his words blurred into each other and all she could focus on was that one word.

She shifted on the sofa and glanced at the cushion beneath which the envelope of divorce papers lurked.

‘No leaving the house?’ she stuttered. ‘Except for exercise.’

‘From when?’

‘From now,’ Michael said. ‘From right now.’

Julie thought of the woman in the car park. She’d be smugly at home with her Baileys now, whilst Julie was stuck here with Michael, the one person she was trying to escape. There was some horrible cosmic irony to this.

‘What about the kids?’ she cried.

He raised an eyebrow. ‘What about them?’ ‘Well, they’ll want to come home, surely.’

‘I doubt that. Sophie will be quite happy snuggled up with Leo in the love nest.’

‘Don’t call it that.’ ‘Why not?’

‘It’s patronising.’

‘It’s nice. And they call it that themselves. Leo even made a sign for the door.’

‘He did? And Sophie let him put it up?’

‘Yep. I saw it when I went round last week to mend their loo.’ Julie just about managed to stop herself grinding her teeth. Their own downstairs loo had been broken for months; what was he doing mending Sophie’s? Leo, her husband of six months, was a potter, for heaven’s sake. He had to be good with his hands, didn’t he? But then it was nice that Michael was spending time with Soph. Julie would have gone with him if she’d known, if he’d bothered to say. She’d been so busy with spring deliveries at the shop that she’d not seen her elder daughter for weeks, despite her only living twenty minutes away. And now, it seemed, she wouldn’t be able to see her for weeks more. Maybe months. It didn’t bear thinking about.

‘The shop!’ she cried.

‘You’ll have to close it,’ Michael said. ‘I can’t.’

‘The PM says that everyone who can work from home should.’ ‘But I can’t.’

‘Why not? You used to.’

Julie leapt up. She could feel panic rising and strode across the room to throw open the doors to the conservatory. She’d taken up floristry just after Adam had started school, leaving her with starkly empty days, and had initially done home commissions from a camping table in this sunny room. She’d been so excited at every order back then, but now the thought of working here instead of in the bustling shop with Clare filled her with dread.

Building up her business had got her out of the dark days a few years ago. What if, without it, she returned to that confused, angry mess of a person?

‘Did he say shops definitely have to close?’ she asked, nodding to the TV.

‘I’m afraid so.’ ‘Great!’

She flung herself down on the sofa again. The divorce papers rustled beneath her and her fingers twitched. Perhaps now was the perfect time to present them to him. At least then they’d know where they stood. At least then they could legitimately avoid each other all day instead of pretending it was just their busy lives that forced them apart. And yet somehow it felt wrong to file for divorce on the brink of a global pandemic; not in the Dunkirk spirit the prime minister was urging. There were more pressing concerns than her marriage now, not the least of them being their children.

‘Briony’s in London, Mike.’ ‘Yes.’

‘Maybe she should come home? It’s bound to be safer in Derbyshire.’

He shook his head. ‘I doubt she’ll do that, Julie. She’s a—’ ‘Biochemist, I know.’

God, did she know. Michael never stopped going on about it. She could still remember how pleased he’d been when Briony had shown scientific inclinations like his beloved parents, both research chemists. But it wasn’t such good news now.

‘Surely they’ll shut down her lab?’ she said.

‘Doubt it. They’ll need them all for research and she’ll be invaluable. She did her dissertation on vaccinology, remember?’ ‘Of course I remember!’ She didn’t, not really. She’d never taken the same meticulous interest in the intricacies of Briony’s scientific progress as Michael, but she was still very proud of her middle child. And very worried about her. ‘Even so, she’d be safer here.’

‘She would,’ Michael agreed sadly, ‘but I doubt that’ll make much difference to Bri.’ He glanced at the TV, where Lockdown was still scrolling along the bottom in red, then back to Julie. ‘Is this really happening, Jules?’

Her breath caught at the pet name. He hardly ever called her that these days. Hardly ever called her anything.

‘Hard to believe, isn’t it?’

‘Together we will beat this,’ the PM was insisting from the TV, but Julie wasn’t sure she liked the look of her own personal ‘together’. If she was going to be stuck in the family home, it would be better to have at least some of the family here too. She should speak to Adam. They’d already cancelled school exams and now they were saying universities were shutting down. Their youngest child would have nowhere to live bar here, thank God. ‘I’m going to call Adam,’ she said. ‘If they’re shutting the universities, he’ll have to come home’

Michael nodded, his face softening. ‘Good. Yes. That would be good. Nice to know one of them is safe.’

She gave him a weak smile. At least they had their love for their children to hold them together in these strange days. It was a gossamer web now, but webs were surprisingly strong. She picked up her phone, flicked to her favourites and swiped on her son.

‘Mum. Hi.’

‘Hi, sweetheart. How’s things?’

‘Mad! They’re closing the uni down. It’s chaos. No idea what they’re going to do about finals. I need those exams to qualify as a surveyor.’

‘What are they saying?’

‘No one’s sure yet. I think it might go on our continual assessment marks, so I should be just about OK.’

‘Just about?’

‘Come on, Mum, everyone has a couple of bad assignments.’ Julie bit back the obvious response; now was not the time. ‘When will you know?’

‘No idea. The lecturers are going to have to work on it, I think. Still – no exams, hey? Bonus!’

She could hear him smiling down the phone. He was a sunny child, Adam; always had been. It would be good to have him home.

‘When are you coming back, then? Do we need to fetch you? Surely even in a lockdown we’re allowed to pick up our own son?’

‘Erm . . . ’ Something in his voice changed. She heard it as loudly as the crunching of rusty gears.

‘Adam?’

‘I’m not sure, Mum.’

‘Not sure if we’re allowed?’

He swallowed audibly. ‘Not sure if I’m coming back.’ ‘What?’ She felt Michael staring at her and instinctively turned away. ‘What do you mean, Adam? Where else will you go?’ ‘I’m thinking maybe to Chelsea’s place.’

‘Chelsea’s?’ Julie pictured Adam’s girlfriend, a bubbly blonde from somewhere in Kent. ‘She has a place?’

An awkward pause.

‘No. But, er, her parents do.’ A chill ran down Julie’s spine.

‘You’re going to her parents’ house?’

‘Maybe. I don’t know yet, Mum. But if we’re going to be locked down for ages, I’d like to, you know, be with her.’

‘Right. Course. Yes. I didn’t realise it was that serious.’ ‘Mum, we’ve been going out for three years.’

‘Is it that long? Right. Good. Well, how about Chelsea comes here? There’s loads of space with just me and Dad. Sophie’s got her own place, and Briony will have to stay in London.’

‘I know. I spoke to her earlier.’

‘You did?’ It always confounded Julie when her children spoke to each other. She loved it, but it was odd too that they had connections that didn’t revolve around her. Stupid really. ‘How is she?’

‘Focused on her work. You know Bri – she relishes a challenge.’

‘She does. I just hope she’s safe.’ Her voice caught and he must have heard it.

‘Are you OK, Mum? Is Dad?’

She pulled herself together, forced herself to be cheerful for him.

‘We’re fine, sweetheart. And as I said, there’s loads of space here if you and Chelsea want to come up. It’d be lovely to have you.’

Silence. She could hear shuffling sounds and suspected Adam’s girlfriend was next to him and that they were exchanging some sort of looks.

‘That’s very kind, Mum,’ Adam said eventually. ‘But Chelsea’s parents are all set. Her little sister is lonely.’

‘I’m lonely.’ It was out before Julie could stop it. She bit furiously at her lip. ‘Not lonely. I don’t mean lonely. Just that I’d like to see you.’

‘I’m sorry.’ His voice tightened. ‘We’ve made plans. And Chelsea’s family are nice. Normal, you know.’

‘Normal?’ The word iced around her heart. ‘What do you mean? Are we not normal, Adam?’

‘Course. Course you are. I didn’t mean we’re not normal. They’re just fun. Not that you’re not fun, obviously. It’ll just be good to, you know, see somewhere different.’

‘Different? Right.’

He wasn’t coming home. Her baby boy wasn’t coming home to her; her nest truly was empty. Julie clutched her spare hand into her hair, as if she might hold onto herself that way, but suddenly her whole body seemed to be shaking, the way it had been threatening to do ever since she’d stepped out of the lawyer’s offices.

‘Mum?’ Adam sounded scared now.

‘It’s fine, Adam,’ she forced out. ‘You have fun with Chelsea and her family. That’ll be nice for you. They live by the sea, right?’

‘Right!’ He snatched at this. ‘At least we can get out on the beach, hey?’

‘I guess so. Lovely. That’ll be lovely.’

‘Yes. And we’ll come and see you as soon as we can, as soon as all this is over, yeah?’

‘Course.’ She had to end this wretched conversation before she said something she regretted. Or cried. ‘Great. Give her my love and say thank you to her parents from me, will you? From us.’

‘I will. And we can FaceTime and stuff, yeah?’ He was falling over himself to be nice to her now and she couldn’t stand it.

‘We can. Got to go, Adam. Take care, sweetheart.’

‘You too, Mum.’ And he was gone, doubtless to pour out his relief to blinking Chelsea and her ‘normal’ family.

Julie looked at Michael, sitting straight-backed in his stupid armchair.

‘He’s not coming?’ he asked. She shook her head.

‘So it’s . . . just the two of us, then?’

Julie drew in a deep breath and felt the divorce papers crackle beneath her.

‘Just the two of us,’ she confirmed.

Never had those words sounded more ominous.

Chapter Three

Michael Marshall went into his garage, closed the door behind him and drew in a long, deep breath. Julie was tearing around the house like a whirlwind and he was scared of being caught up in the centre of the rush. She’d always had so much energy, his wife. She was like a dynamo, generating it out of seemingly nowhere. When they’d first been together, he’d watched in awe, loving the way she swept him off his utterly grounded feet and into adven- tures and experiences he’d never known possible. These days, though, she mainly just made him feel tired. And weirdly tearful. He pushed himself away from the door and whipped the cover off his Moto Guzzi motorcycle, once his dad’s pride and joy and now his own. He’d cried when his dad, Ken, had died of a sudden heart attack. He’d cried buckets. And Julie had held him close and wiped his eyes gently and told him to ‘let it all out’. So he had. But that had been different from the strange half-tears that seemed to niggle up out of him at the strangest times these days. That was why the bike was good. You could cry on a bike, because who could distinguish tears from the moisture pushed out of your eyes by good old-fashioned speed?

He patted the Guzzi. She was called Gertie – his dad’s choice – and she was a V7 Sport, a classic. He’d love a ride out right now, but he was waiting on a new oil pump from Gary at the garage, and until that came, the poor old girl was grounded. Locked down – like him.

Michael sighed and went over to his spanner set, running his fingers along the perfectly ordered tools to find the right size. He wasn’t sure why he was bothering, but the action was reassuring all the same. So many times he’d mended this bike. Italian engi- neers knew a bit about style but rather less about reliability, and he wasn’t sure there was any part of the engine left from when his father had gifted Gertie to him on his eighteenth birthday. That made him sad, but the body was still the same, de-rusted, repainted, but still there. Still beautiful.

‘Soon have you sorted, Gertie old girl,’ he muttered. ‘Soon have you back on the road.’

Except would he? If they were in lockdown, would Gary be able to get him the pump? He’d have to call him, push for it whilst he still could. Then at least he’d be able to head out for a ride if things got too much. If Julie got too much.

He thought of his wife and was hit by the all-too-familiar wave of sadness that seemed to be the only emotion he could usefully call up towards her these days. Things were very, very wrong between them. He might not be the most astute of men, but he wasn’t stupid.

Silently he prayed that the florist’s wouldn’t have to be shut for too many weeks. Julie loved that shop. She’d lavished so much care and attention on it since she’d opened it back in 2006, and it had done very well. She’d won awards, been featured in magazines and, of course, turned quite a profit. But who was going to buy flowers in a lockdown?

‘Everyone,’ he heard Julie’s voice say in his head. ‘If you’re shut inside, you’ll need beautiful flowers to keep you sane.’

They didn’t seem like a necessity to Michael, but as she’d pointed out to him on many occasions, he was useless at appreciating beautiful things. Except for the bike, of course. Even Julie had admitted that the bike was beautiful. He could still remember her tumbling out of a café in Budapest on the very street corner where he’d chosen to stop to glug down some water. She’d come bouncing over to admire Gertie in tiny shorts and the most glorious red top, and that evening she’d turned up at his campsite claiming she’d wanted to see the bike again. Hours later, straddling him, she’d admitted that perhaps he’d been the greater draw. He’d not been able to believe his luck. In many ways, he still couldn’t.

Julie was a whirlwind, yes, but a warm, colourful, exotic one. She’d brought light to his rather dull life, and if it had sometimes dazzled him, he’d been happy to take that. A studious only child of relatively serious parents, he’d never really experienced the sort of exuberant, impulsive approach Julie took to life, and he’d loved it. They’d all loved it. When his dad had died just two weeks shy of their wedding, Julie had wanted to cancel but Michael and his mum had refused.

‘We need happiness,’ he’d told Julie through tears. ‘We need it or we’ll both go under. You are that happiness.’

It had been true. Julie had got him through that terrible time with her love and her care and her natural joy. The wedding had been bittersweet but beautiful all the same, and they’d had a wonderful honeymoon on the bike, even if they’d had to cut the trip short to be back for the funeral. They’d never made it to the Greek islands, but it hadn’t mattered. They could have gone to Skegness and he’d have been happy as long as she was there. Suddenly restless, he jumped up and opened the door. The sun was shining across the lawn, lighting up the increasingly

shaggy grass. He’d have to mow it.

‘Sorry, Nibbles,’ he apologised to the rabbit, which, true to its name, was nibbling away at the long fronds trapped beneath its cage. How old must the creature be? He grinned at the memory of Briony’s war of attrition to secure her beloved pet. That girl knew how to achieve a goal, be it a rabbit or a biochemistry degree. She got that from his mother, Bett, who’d always had the same focus and scientific skill as her middle grandchild. He must call her. She’d be all alone in the house, having steadfastly refused to so much as look at another man since his dad’s death, and at her age that was a worry.

The sudden slam of a door inside the house made him jump. Julie. She always slammed doors, more teenage than their teenagers.

‘Michael?’ To his surprise, she shouted out for him. He went back to the bike, crouching instinctively behind it. ‘Michael, are you there? Clare says we should do online flower deliveries. She wants to paint the logo on her car and I thought you might have some paint we could—’ The garage door flew open and there she was, exuberant in a bright yellow jumper. ‘Michael? What are you doing down there?’

He peered up at her. ‘Mending Gertie, of course.’

‘Of course.’ She peered at the Guzzi and gave a little sigh, then looked up at his shelves. ‘Paint?’

He put the spanner down on the side and fetched the little pot of metallic red he used to touch up Gertie’s glorious bodywork. In truth, he was reluctant to hand it over in case he couldn’t match her colour again, but even he could see that would be churlish.

‘Here.’ He passed it to her.

‘Thanks.’ She took it and tapped on the lid, unusually twitchy. ‘Got to do what we can to keep the business going, right?’

‘Right. So you’ll, er, still be going into the shop?’ ‘If I can.’

‘Is it allowed?’

‘If we use it as a workshop rather than a retail unit, yes.’ ‘I see.’

‘And if it’s not, we might do it from here. Like you suggested, remember?’

Had he? What an idiot! He felt suddenly nervous of his wife. She’d always had energy, yes, but she’d never been quite this assertive. When she’d come home earlier and asked to talk, he’d been scared of what she was going to say and he had to admit he still was. He looked around his garage. Perhaps he could move in here permanently? Or perhaps . . .

‘Actually, Julie, I’ve been wondering if I ought to go and stay with my mum.’

‘Really?’

Had he imagined it or had her eyes lit up? His chest squeezed. ‘I’m worried about her, all on her own. She’s eighty-two, you know.’ ‘I know.’

‘Vulnerable.’

‘Oh, come on, Michael. Bett’s about as vulnerable as a Sherman tank.’

‘That’s not true. She’s mentally strong, yes, but she’s in the high-risk category. If she caught the virus . . . ’

Julie sucked in a loud breath, looking instantly contrite. ‘You’re right. Sorry. I didn’t mean . . . You know I love your mum.’ They stood there facing each other, the old clock on the wall ticking loudly between them. ‘So,’ Julie said eventually, ‘have you called her?’

‘Not yet. I thought I’d check with you first. See if you, you know . . . ’ The words ran out. ‘Needed me here’ he’d been going to say, but it already sounded ridiculous in his head. Julie didn’t need him here. If he was honest, she hadn’t needed him for years.

‘I’m sure she’d be grateful to have you,’ she said stiffly. He nodded, picked up his phone. ‘I’ll . . . ’

‘Right.’

She backed out and the door banged behind her. Trying not to flinch, he found his mum’s number, pressing it before he changed his mind. Sitting himself down on the Guzzi, he settled into the perfect curve of the worn leather seat.

‘Michael! How lovely. How are you? Isn’t this all complete madness?’

Michael blinked at his mother’s cheery tone. He’d half convinced himself of the vulnerable thing, but here was Bett Marshall, as formidable as ever.

‘It’s very strange, Mum, yes. I’m worried about you.’

‘Me? Heavens, why on earth are you worried about me? Oh, because I’m “elderly”?’

‘Well, yes. I know you’re in great health and all that, but this virus can be nasty if you’re . . . ’ He hesitated, suspecting she’d hate ‘vulnerable’ even more than ‘elderly’.

‘A bit knackered anyway?’ she offered cheerily. ‘Thanks, love, but I know that. I’m not stupid. Thirty years as a research chemist has taught me a bit about this sort of thing and I’ve not lost my faculties yet.’

He laughed. ‘I know that, Mum. You just tend to think you’re invincible.’

‘And tend to prove it too.’

‘Yes, but . . . ’ No point in pursuing this line further. ‘Look, Mum, I was thinking perhaps I should come and stay with you whilst all this is going on.’

‘Stay with me? Why?’

‘To look after you, do your shopping and stuff. It looks as if they’re going to stop people over seventy going out altogether, so I thought if I was there then—’

‘Stop right there, Michael. I’m ahead of you.’

‘What?’

‘I had a long chat to my mate June, who was an immunologist, and she’s explained it all to me. Best to keep us oldies well out of the way so we don’t get complications and clog up the hospital beds.’

‘It’s not like that, Mum.’

‘Course it is. And quite right too.’

‘But I don’t think you should be on your own.’

‘Me neither, Michael, which is why I’m moving in with Carol and Liz.’

‘You’re what?’

‘Moving in with Carol and Liz, my friends from bridge. Carol has the most enormous house and since her husband died she’s been rattling around in it, so there’s loads of room for Liz and me. We’re going to call it the share home. Instead of care home – get it?’

‘I get it, Mum.’

‘All we’ve got to bring, apparently, is clean undies and three different types of gin. Good or what?’

Michael stared out the window. Mr Nibbles was hopping gently around his run. Was it Michael’s imagination, or were the rabbit’s back legs looking a bit creaky? He shivered.

‘That’s great, Mum. Sounds . . . fun.’

‘Doesn’t it? She’s got a pool, so I can keep fit. And a hot tub. And the most enormous garden I can potter in. And Liz’s son is the manager of the local supermarket so he’s going to make sure we get loads of food delivered. We won’t have to go out for months if that’s what it takes. Really, you needn’t worry about me at all.’

‘No. Clearly not.’ ‘Michael? Are you OK?’ ‘Me? Of course.’

‘How are things there? Kids OK? Are they coming home?’

‘No. They’ve all got busy lives.’

‘Indeed. So it’ll be just you and Julie then?’ ‘Looks like it.’

‘And is that OK?’ She sounded suddenly tentative – so unlike her normal self.

‘Of course it is, Mum. Why wouldn’t it be?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. It’s a funny time of life when the kids first move out. It can be . . . disorientating.’

‘Can it?’

‘Oh, yes. I don’t think your father and I ever argued as much as we did when you went to university.’

‘You argued?’

She laughed softly. ‘We weren’t perfect, Michael. No couple is. Talk to her.’

He blinked. ‘To who?’ ‘Julie, of course. Your wife.’ ‘Right. Yes. Of course.’

‘God, I remember you two when you were first dating. I’d never seen you so happy. She wasn’t the woman I’d ever have imagined you coming home with, but the moment I saw you together, I knew she was spot on.’

‘You did?’

Bett tutted. ‘Will you stop asking anodyne questions, Michael. Of course I did. So talk to her. If nothing else, this lockdown business will mean you have time for that.’

‘Yes.’ Michael grimaced. He watched out the window as Julie came out of the house with some carrot peelings for Mr Nibbles. As was her wont, she simply chucked them in the general direction of the cage, so that only half of them actually went through the bars. They’d get caught up in the mower if he didn’t watch out.

‘Michael?’

‘I will talk to her, Mum. And, er, you have fun with Carol and Liz.’

‘Oh, I will! I’ve found the best marmalade gin. They’re going to adore it. Take care, love. Speak soon.’

‘Speak soon,’ he echoed, but she was already gone, off to pack undies and spirits and head to Carol’s mansion.

He watched as Julie paced around the garden and then, to his surprise, turned back to pick up the loose carrot peelings. He saw her bend to say hello to the old rabbit and caught a glimpse of the girl he’d so very happily married nearly thirty-five years ago. He wished he could go back to when it had all been simple, but even the best engineer couldn’t build a bridge into the past. Somehow he had to find a way forward. Somehow he had to work out what had gone wrong between them and undo the damage he knew he’d done six months ago at that other, far more tangled wedding, where things had come to a head in such an unforgivably ugly way.

'An uplifting love story that could not be more timely'

Eva Woods

'Must read'

Bella

'It hooked me from the start'

Sue Moorcroft

'I absolutely loved it'

Ella Dove

'So relatable, so emotional, so good'

Tracy Bloom

*

What happens after Happy Ever After?

After thirty-four years of marriage, Julie and Michael's grand romance has . . . fizzled. More like housemates than husband and wife, Julie wonders whether it's time to give up on their love story, once and for all.

A lockdown - just the two of them - seems like it might be the final straw.

But, when stripped of all distraction and forced to meet eyes across the dinner table every night, unexpected sparks begin to fly . . .

Can Julie and Michael ever find a way back to who they used to be?

Or could this be the start of a whole new love story?

*

A joyful and uplifting romance about second chances and rediscovering love when you least expect it. The perfect feel-good read that will make you laugh, make you cry and lift your spirits.

Readers are falling in LOVE with Just the Two of Us . . .

'Utterly brilliant . . . It made me laugh out loud and also moved me to tears, will definitely recommend this book to everyone I know'

'Absolutely loved this story - couldn't put it down!'

'A super novel . . . Amusing in places, sad in others, this really is the novel to read now'

'I was completely immersed in the story from the start!'

'Made me smile, laugh and root for the characters . . . the perfect read for the current times'

'A wonderful love story! Funny, moving and feel-good . . . had me laughing out loud'

'Feel good story in unprecedented times!'

'Very enjoyable . . . A lovely romance plot'

'I was hooked from the start'

'Highly relatable, heartwarming and emotionally charged'

'A heartwarming story during a really unusual time of our lives'

'Emotional and at times sad, there is also plenty of humour to lift you through. Definitely recommended'