Dialogue Books | Alex Allison on the artists that inspired The Art of the Body

Today we welcome author Alex Allison to the blog in celebration of the release of his debut, The Art of the Body, in paperback form! He’s taking the stage to share a list of the disabled artists who went some way to inspire the narrative of his novel.

Throughout Art History, visual artists have been fixated by the human form. The body is the primary and inescapable subject and vehicle for all aesthetics. But all bodies are not created equal. The body variously has the capacity to both excite and revolt, to titillate and nauseate.

In my debut novel, The Art of the Body, we follow the artistic practice of Sean, an art student with cerebral palsy, who seeks to explore the limits of his own body through art. With the assistance of his carer (and the novel’s narrator), Janet, Sean is bound and photographed in various contortions, some evocative of torture, others redolent of more biblical and classical themes. As an Irish artist from a single parent family, Sean’s work engages with themes including class and colonialism.

From Frida Kahlo, to Michelangelo, Goya, and Van Gogh, there is no shortage of artists whose disabilities have informed their work and practice. It is my privilege to share with you three artists with disabilities who shaped my own creation of Sean.

To this day, much of the critical commentary around Judith Scott refers to her as an Outsider Artist or Naïve Artist – a label given to many artists with disabilities or mental illnesses who bypassed formal training. The term has come to imply a lack of directed artistic intent, which many feel misrepresents artists like Scott.

Scott was born into a middle class family in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1943, along with her twin sister Joyce. Judith was affected by Down Syndrome, and was left deaf by a bout of Scarlet Fever as an infant. This deafness went undiagnosed well into her adult life. Judith was deemed ‘uneducable’ by various state institutions, and suffered immensely following her separation from her twin sister, becoming alienated and developing behavioural problems. After some thirty-five years of separation, Joyce won custody of her sister after a long legal battle, and moved her to California where she was enrolled at the Creative Growth Arts Centre, a singular institution at the time, providing studio space for disabled artists.

During a fibre class intended to teach stitching, Judith began creating spontaneous sculptural bindings. Her gifts were immediately recognised and encouraged – working with found objects – most often stolen from the centre and other students, she created amorphous organic shapes. These yarn cocoons are highly evocative of native American folk art. Many of these pieces alluded to her experience as a twin. Paradoxically, Scott found freedom through bindings, engaging with a great sense of play and care to her work.

Austin’s philosophy on photography is that the best work involves ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

Following a long illness that left her disabled, Austin describes first engaging with her wheelchair as ‘tremendous new freedom’ and an ‘enormous new toy’. Despite relishing this freedom, she became acutely aware of how other people’s expectations and perceptions of her had become shaped by the chair and her disability, which in turn affected what she internalized about herself.

In response, Austin began to create art works that harness her initial feelings of freedom and play, through reconditioning the familiar via creative expression. Her underwater wheelchair pieces combine a perceived limiting technology (power chairs) with a freedom enabling technology (scuba gear), creating a brilliant and beautiful schism that subverts our expectations in aesthetically dazzling ways.

Like Sean, Shonibare was educated at what is now Central Saint Martin’s Art College. A multidisciplinary artist, Shonibare relies on assistants to help craft his artistic visions. One side of his body is paralysed and he uses a wheelchair.

Through his work, Shonibare explores questions of race and class, in relation to his dual nationality as British-Nigerian. His trademark is a brightly coloured batik fabric, which is materially tied up in colonial trade routes, spanning from Indonesia, to the Netherlands, to West Africa.

Shonibare uses his pieces to confront, reflect and transform the world. His art is deeply complex and playful, enchanting through vibrant and arresting imagery, colour and form. He achieves this whilst remaining inherently political, drawing on the past to confront the present.

Shonibare has stated that his excitement for his work is his primary motivation in finding solutions to the restrictions his disability.

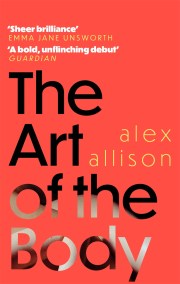

The Art of the Body

by Alex Allison

'A bold, unflinching debut' GUARDIAN

'Brutal, tender, philosophical, visceral, complex and so well written' EMMA JANE UNSWORTH

Maintaining one person's dignity comes nearly always at the expense of someone else's. I have learned this for you.

Janet is caught between care work and caring for herself. Her life revolves around Sean, a talented fine art student, living and working with cerebral palsy. Both Janet and Sean are new to London and far from their families. Both are finding a means of escape through pushing their bodies to the limit.

When Sean is faced with an unexpected and deeply personal tragedy, Janet must let her guard down at last and discover what she's prepared to fight for.

The Art of the Body is a novel about dignity and intimacy, tenderness and brutality, unafraid to explore uncommon bodies in unusual ways.

'Raw and powerful' IMAGE