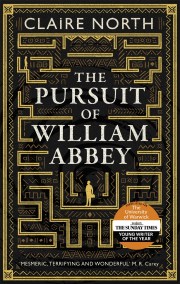

The Pursuit of William Abbey by Claire North

‘I was cursed in Natal, in 1884. Cursed by truth and by blood. The shadow took to me, and we have been together since.’

From the bestselling and award-winning author of The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August and 84K comes a powerful new novel about a young man haunted by a ghost from his past, and by the dark crimes committed in the name of the British empire.

CHAPTER ONE

France, 1917

The truth-speaker was tall as a stretcher, thin as a rifle. He wore a black coat that stopped just above his knees, a tie the colour of drying blood, a black felt Derby hat and a pair of horn-rimmed spectacles on a string. He carried a brown doctor’s bag in one hand, and a military-issue shoulder sack. Behind him the sky popped with cannon, the sound rolling in half a minute later like the wash of the sea. His curse can’t have been too near then, because he looked me in the eye and lied.

“My name is Dr Abbey,” he said. “I’ve been sent by HQ.”

I never asked to check his papers. Matron was so relieved, she babbled.

Sister Beatrice had to move from her room. A doctor needed better quarters than a nurse. She, being senior to me and Helene, immediately claimed ours. The window was small and let in the winter air, but it was in a good position on the south side of the building and there had been no rats seen for nearly three months.

Me and Helene was pushed into a tiny, lime-washed, spider-scuttling den in the eastern corner of the house. We dragged my bed on its side through the corridors, shuffling in socks, trying to keep the scraping of metal on wood from waking the patients below. In whispers we grumbled about this new intruder on our routines, and Helene wrote a letter to her Ma saying it were all terrible and she wanted to come home, but she never sent it, and I put my head down on my pillow with resentment in my heart, and slept badly, and woke for a moment frightened, and was surprised I could still be scared.

When I went down for the afternoon shift, I found Dr Abbey about his rounds, drifting from bed to bed with the same expression on his face for every patient, whether they were hopeful of recovery or waiting for death. He did not smile, did not frown, but with every man he stopped, looked into their eyes as if he were staring down the barrel of a gun, asked a few questions, nodded at a couple of replies, then moved on without a word.

In this way – cold, almost bored – he was just another typical bloody doctor. On the battlefield the surgeons only saw flesh, never the men they cut open. We were all getting good at not seeing eyes. It were the sisters who carried the bodies to the carts, stripped the beds, put the unfinished letters to family in a bag, trimmed off the corners that were stained with blood. We picked up the limbs the surgeons cut and put them in a box: an arm without a hand; a leg hanging together by a stitch of muscle at the knee. We cleaned brain off the knife and picked out bone from between the teeth of the saw, held the boys down when the ether ran low.

When I first came to the battlefield, I would listen to the cannon and think I heard the end of the world. There was one other doctor at the house. Dr Nicolson had been sent to us at the Jardin du Pansée, six miles back from the line, after being caught inhaling ether. Matron kept the cupboards locked tight when Dr Nicolson did his rounds. The arrival of Dr Abbey at last let Nicolson indulge in his love of Indian gin, shipped to him by his mother every six weeks via a small Portuguese man who he called “cousin” and who had not a word of English. When the gin came late, he would stand vigil by the garden gate; if it came early, he might share the smallest of drams, and then look immediately regretful as we drank it down, and hide the bottles after.

If Abbey cared, it didn’t show. He arrived in shadow, and in shadow he stayed, and in silence we performed our duties, numb to neither cannon or the cries of men to pull us from our thoughts.

CHAPTER TWO

On his second night in the Jardin, Lieutenant Charlwood came down with a fever. We sisters took turns by his bed, waiting. I had been trained by the Nightingale sisters, and back in Manchester I could tie bandages, staunch bleeding, prepare saline and spoon-feed a mother and her freshly born babe; but here only God chose which man with his face burnt to a plum or what soldier with his gut ripped out might by a miracle live or die. We were powerless before pus and poison, and when the blind men came off the field, faces burst with mustard gas, blisters the size of apples popping from their skin, what could we do? The Jardin was a place for men to die, or if they did not, they would be sent back to England, no longer fit to fight.

I knew there was little I could do except pray for Charlwood as he clawed at his sheets, bloody eyes bulging, tongue pushing in and out of snapping yellow teeth as he groaned at the night. I knelt by his side and prayed, and knew I didn’t believe no more, and that there weren’t no God listening, but felt as how I should try. We all liked Charlwood. Like many men, he neither looked at nor spoke about his injuries, but laughed and smiled and joked that he was in a bit of a pickle, and wondered if the ladies would mind – all the usual talk of brave boys who didn’t know that we had heard this bravery from a thousand other broken ones before.

That night, the truth-speaker came, no knock at the door. In socks, his black coat pulled over striped red flannel pyjamas, right arm wrapped tight across his body against the cold, left carrying an oil lamp by its curved brass handle. His dark brown hair was combed back from his face, turning up long streaks of grey from beneath the surface. His beard was trimmed and flecked with the same pallor – was he old before his time, a man in his forties marked by war? Or was he a slow ager, already into his sixties and hiding beneath hat and hair? He had eyes the colour of my grandad’s dining table, all polished and gleaming in the light, which vanished beneath thick eyebrows when he looked down, then popped wide like an egg when he raised his head. Like all of us, he had no real meat on him, and the skin hung loose beneath his jaw, and there was nothing – not hook nose nor protruding ear – that gave him any feature that was remarkable. If the men who drew the caricatures of native peoples of the world had wanted to draw an average Englishman, they could have drawn him.

I stood when he entered the room, but he gestured me down with a finger to his lips. Putting his lamp on the nightstand by Charlwood’s head, he examined his eyes, felt for his pulse, the temperature of his skin, smelt his breath and his sweat, rolled back his gown, examined the edges of the bandages around his hips, sniffed at stumps, nodded, returned the gown and pulled the blankets back up again, pushing the edges in around his torso like a parent tucking in a child.

Then he sat.

And watched.

And waited.

I didn’t know what to make of this. The silence of the lonely night was a ritual for every sister who kept vigil, and we did not share it. We waited alone with the dying men; the doctors never came, and only the women watched.

Yet now he sat there, and in his silence it seemed that he was admitting the thing that the nurses all knew, and the doctors never said – that we were powerless.

The cannon were quiet that night. Sometimes they were quiet because they were out of shells, or the generals had lost interest, or there were other battles somewhere further down the writhing line from sea to mountain where the bigger guns were blasting. Sometimes they were quiet because the men were climbing into the dark, crawling towards the machine guns. You never could tell, unless the wind blew right to carry the sound of the dying. We sat by lamplight watching the soldier groaning in his bed, and neither me nor Abbey said a word, until after an hour, or perhaps two, he left as quietly as he had come, and closed the door behind him.

CHAPTER THREE

When this war began and I were in the field hospital, I would gossip with the sisters about the latest pretty young doctor come to the tents, though Lord knows I couldn’t have cared less for them. It was a ritual we performed for every young man who arrived with his bones intact and light in his eyes. We giggled like we were home in England, laughing at private jokes and fantasies, forgetting for a little time where we were.

There was none of that in the Jardin. Those of us sent to this place were just performing functions, without feigning life, without noting death. It were meant as a kind of respite. In the Jardin, Matron said, there was no struggle. There was no terror, no expectation, no story to be told. There was just the day passing, and the morning truck to deliver the living and the evening truck to take away the dead.

Once, it had been a stately home, a place where French maidens had picnicked in the summer sun while artists in berets and white smocks painted the lilies on the water. In spring the garden was a quilt of pale violet and lavender, pinks and pockets of creamy yellow. In summer the shrubs broke out into wine red and royal blue, and we would sit and watch the evening primroses open on the quietest nights, when you could imagine the war was some other place.

It was winter now, felt like it had been winter for ever.

On the next night I sat with Charlwood, waiting for him to die, Abbey came again. I was holding the soldier’s right hand, squeezing it tight at the moments of the worst pain. Then Abbey took his left, and I nearly let go. There was something inappropriate about the thing, like through the injured man we were sharing an unclean, intimate touch.

We waited.

I wanted to ask questions, but they all seemed inane.

I thought I might cry, and hadn’t realised how much harder it were to sit with someone else than to sit alone. I held on to Charlwood’s hand, and found that I wanted him to live, and didn’t know as how I had that sort of feeling in me no more. And after a few hours, he seemed a little quieter, and the doctor went back to bed. On the third day, the fever broke, and on the fourth, as Abbey made his rounds, Charlwood opened his eyes and looked up into the doctor’s face and said, “I know you, don’t I?”

Abbey simply shook his head, and walked on.

CHAPTER FOUR

We were having dinner when Captain Fairchild died. It happened so fast; Helene ran in on the verge of tears, and though Matron insisted that a sister never run, Abbey was already out of his chair and sprinting down the hall before Helene had finished rattling her words. Fairchild was gasping, his lips turning blue, eyes rolling from side to side in search of remedy. Even Nicholson was roused at the fuss, and stood in the door watching as we tried raising him up to breathe better, Matron wheeling in the heavy gas mask and gas cylinder. But Abbey just shook his head as Matron moved to fix the mask over Fairchild’s face, and the Captain saw it, and he like everyone else knew he was going to die. I don’t know if that made the next three minutes in which he gasped for life easier; perhaps it did. He passed out before his heart stopped, and we laid him back down. He had been due for discharge back to England the next day.

That night, I stood in the garden beneath the great-leafed fig tree as the rains came. The cannon were a half- hearted rumble, grunting without order or meaning. The rain, when it burst, pushed all other sound away, filling the night with water on stone, water on soil, water on furry leaf, water dripping off needle and spine, on metal pipe and tapping on dirty glass. I put my hands out beneath the reach of the tree and listened to water on skin, and wondered who I would be when I went home.

I don’t know how long he’d been there, or if he’d even arrived before me and I hadn’t seen him in the shadows, but I heard his feet on wet leaves and thick black soil, and jumped, pulling my shawl around me to see him half caught against the light of far- off cannon and slithered moon.

“Apologies, Sister,” he mumbled. “I didn’t mean to intrude.”

“No.” A half-mutter, pulling my shawl so tight it bent my shoulders forward, stepping a little further from him, back to the house, head brushing a low- hanging leaf. “Of course.”

By now, I was almost used to his strangeness. We had kept vigil over Charlwood, and he had watched as we prepared the body of Fairchild for the undertaker’s cart, saying nothing. I felt no need to show him the usual deference due a doctor. Now, we were two people watching the rain.

When I spoke, therefore, I were surprised to hear myself, and even more at how clearly my voice pushed through the gloom. “Fairchild wasn’t phosgene.”

“No. If it was the gas, he would have been hit sooner. It was a pulmonary embolism. There was nothing to be done.” Then, an afterthought, a flicker of something human through the doctor’s mask: “It wasn’t anyone’s fault.”

“It was the enemy’s fault,” I replied flatly. “It was the war.”

We watched the rain.

His eyes were somewhere else, his voice talking to a different place. “The woman I love is alive and well. The children lived. The shadow will not come.” These words sounded almost like prayer, a ritual of speech. Being spoken, he shook his head, as if working out a fuzzy notion, and declared a little louder, “Sister Ellis. You know that she is waiting for you, that she forgives you. But in its way, her forgiveness makes it harder for you to go home.”

My heart is marble in my chest. My skin is stone, cleansed with rain. The cannon are thundering at the skies but haven’t made a dent yet.

Abbey nodded once, satisfied with his pronouncement, and walked into the house, and didn’t look back.